-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 37

gfm guide

This guide aims to bridge the gap between the absolute Flutter [1] basics and clean, structured Flutter development. It should bring you from the basics of knowing how to build an app with Flutter to an understanding of how to do it properly. Or at least show you one possible way to make large scale Flutter projects clean and manageable.

For people with a basic knowledge of the Flutter Framework. I recommend following this tutorial by the Flutter team [2]. It will walk you through developing your first Flutter application. You should also have a basic understanding of the Dart programming language [3]. No worries, it is very similar to Java [4], Kotlin [5] and JavaScript [6]. So if you know 1 or 2 of those languages you should be fine.

- A brief introduction to the Flutter Framework in general:

- How the underlying technology works,

- how it’s programming style is little different from other frameworks,

- how Flutter apps are structured on an abstract level and,

- how asynchrony and communication with the web can be implemented.

- A showcase of possible architectural styles you can use to build your app and

- an in-depth guide on one of those possibilities (BLoC Pattern [7]).

- How to test your app.

- Some conventions and best practices for Dart, and the Flutter Framework in general.

- My personal evaluation of the framework.

This guide was written by a student in the Bachelor of Science Program “Computer Science and Media Technology” at Technical University Cologne [8], and it was created for one of the modules in that Bachelor. In addition to this, the guide was written in collaboration with DevonFw [9]. DevonFw released a guide on building an application with Angular [10] in May of 2019, this guide is meant to be the Flutter version of that.

The guide is designed to be read in order, from chapter 0 (this one) to chapter 5. Code examples throughout the chapters will mainly be taken from Wisgen [11], an example Flutter application that was specifically built for the purposes of this guide. If you want to search for any specific terms in the guide, you can use this page. It is all chapters of the guide combined into one page. There is going to be a few common symbols throughout the guide, this is what they stand for:

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 📙 | Definition |

| 🕐 | Shortened version (TLDR) |

| ⚠ | Important |

I am basing this guide on a combination of conference talks, blog articles by respected Flutter developers, the official documentation, scientific papers that cover cross-platform mobile development in general and many other sources. All sources used in the guide are listed in chapter 6 References. To put that theoretical knowledge into practice, I built the Wisgen application [11] using the Flutter Framework, the BLoC Pattern [7], and a four-layered architecture.

If you are interested in how this guide was created, how Wisgen was built, how a bridge between a citation software and Markdown was realized, or any other details about the creation process, check out the Meta-Documentation.

This chapter will give you a basic understanding of how the Flutter Framework [1] works as a whole. I will showcase the difference of Flutter to other cross-platform approaches and how Flutter works under the hood. You will also be introduced to the concepts of State [12] and Flutter’s way of rendering an app as a tree of Widgets [13]. Lastly, you will gain an understanding of how Flutter handles Asynchronous Programming and communication with the Web.

Flutter [1] is a framework for cross-platform native development. That means that it promises native app performance while still compiling apps for multiple platforms from a single codebase. The best way to understand how Flutter achieves this is to compare it to other mobile development approaches. This chapter will showcase how three of the most popular cross-platform approaches function and then compare those technics to the one Flutter uses. Lastly, I will highlight some of the unique features that Flutters approach enables.

Figure 1: Native app rendering [14]

The classic way to build a mobile app would be to write native code for each platform you want to support. I.E. One for IOS [15], one for Android [16] and so on. In this approach, your app will be written in a platform-specific language and render through platform-specific Widgets and a platform-specific engine. During the development, you have direct access to platform-specific services and sensors [14], [17], [18]. But you will have to build the same app multiple times, which multiplies your workload by however many platforms you want to support.

Figure 2: Embedded WebApp rendering [14]

Embedded WebApps where the first approach to cross-platform development. For this approach, you build your application with HTML [19], CSS [20], and JavaScript [6] and then render it through a native WebView [14], [17]. The problem here is, that developers are limited to the web technology stack and that communication between the app and native services always has to run through a bridge [18].

Bridges connect components with one another. These components can be built in the same or different programming languages [21].

Figure 3: Reactive app rendering [14]

Apps build with reactive frameworks (like React Native [22]) are mostly written in a platform-independent language like JavaScript [6]. The JavaScript code then sends information on how UI components should be displayed to the native environment. This communication always runs through a bridge. So we end up with native Widgets that are controller through JavaScript. The main problem here is that the communication through the bridge can be a bottleneck that can lead to performance issues [14], [17], [18], [23].

Figure 4: Flutter app rendering [14]

Flutter’s approach is to move the entire rendering process into the app. The rendering runs through Flutter’s own engine and uses Flutter’s own Widgets. Flutter only needs a canvas to display the rendered frames on. Any user inputs on the canvas or system events happening on the device are forwarded to the Flutter app. This limits the bridging between the app and native environment to frames and events which removes that potential bottleneck [14], [17], [18].

You might think that keeping an entire rendering engine inside an app would lead to huge APKs, but as of 2019, the compressed framework is only 4.3MB [24].

Figure 5: Flutter Framework architecture [14]

| 🕐 | TLDR | Flutter uses its own engine instead of using the native one. The native environment only renders the finished frames. |

|---|

One additional advantage of Flutter is that it comes with two different compilers. A JIT-Compiler (just in time) and an AOT-Compiler (ahead of time). The following table will showcase the advantage of each:

| Compiler | What is does | When it’s used |

|---|---|---|

| Just in Time | Only re-compiles files that have changed. Preserves App State [12] during rebuilds. Enables Hot Reload [25]. | During Development |

| Ahead of Time | Compiles all dependencies ahead of time. The output app is faster. | For Release |

Table 1: Flutter’s 2 Compilers [17], [26]

Hot Reload [25] is a feature that Web developers are already very familiar with. It essentially means that changes in the code are displayed in the running application near instantaneously. Thanks to its JIT Compiler, The Flutter Framework is also able to provide this feature.

Figure 6: Hot Reload [25]

If you are coming from the native mobile world and imperative frameworks like IOS [15] and Android [16], developing with Flutter [1] can take a while to get used to. Flutter, other then those frameworks mentioned above, is declarative. This section will teach you how to think about developing apps declaratively and one of the most important concepts of Flutter: State [12].

I will explain the difference between declarative and imperative using a metaphor: For a second, let’s think of programming as talking to the underlying framework. In this context, an imperative approach is telling the framework exactly what you want it to do. “Imperium” (Latin) means “to command”. A declarative approach, on the other hand, would be describing to the framework what kind of result you want to get and then letting the framework decide on how to achieve that result. “Declaro” (Latin) means “to explain” [1], [12], [27], [28]. Let’s look at a code example:

List numbers = [1,2,3,4,5];

for(int i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++){

if(numbers[i] > 3 ) print(numbers[i]);

}Code Snippet 1: Searching through a list (Imperative)

Here we want to print every entry in the list that is bigger than 3. We explicitly tell the framework to go through the list one by one and check each value. In the declarative version, we simply state how our result should look like, but not how to reach it:

List numbers = [1,2,3,4,5];

print(numbers.where((num) => num > 3));Code Snippet 2: Searching through a list (Declarative)

One important thing to note here is, that the difference between imperative and declarative is not black and white. One style might bleed over into the other. Prof. David Brailsford from the University of Nottingham argues that as soon as you start using libraries for your imperative projects, they become a tiny bit more declarative. This is because you are then using functions that describe what they do and you no longer care how they do it [29].

| 🕐 | TLDR | Imperative Programming is telling the framework exactly what you want it to do. Declarative Programming is describing to the framework what kind of result you want to get and then letting the framework decide on how to achieve that result. |

|---|

Okay, now that we understand what Declarative Programming is, let’s take a look at Flutter specifically. This is a quote from Flutter’s official documentation:

“Flutter is declarative. This means that Flutter builds its user interface to reflect the current State of your app” [12]

Figure 7: UI = f(State) [12]

In Flutter, you never imperatively or explicitly call a UI element to change it. You rather declare that the UI should look a certain way, given a certain State [12]. But what exactly is State?

| 📙 | State | Any data that can change over time [12] |

|---|

Typical State examples are user data, a user’s scroll position within a list, a favorite list.

Let’s have a look at a classic UI problem and how we would solve it imperatively in Android and compare it to Flutter’s declarative approach. let’s say we want to build a button that changes its color to red when it is pressed. In Android we find the button by its ID, attach a listener, and tell that listener to change the background color when the button is pressed:

Button button = findViewById(R.id.button_id);

button.setBackground(blue);

boolean pressed = false;

button.setOnClickListener(new View.OnClickListener() {

@Override

public void onClick(View view)

{

button.setBackground(pressed ? red : blue);

}

}); Code Snippet 3: Red button in Android (Imperative)

In Flutter, on the other hand, we never call the UI element directly, we instead declare that the button background should be red or blue depending on the App-State (here the bool “pressed”). We then declare that the onPressed() function should update the App State and rebuild the button:

bool pressed = false; //State

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return FlatButton(

color: pressed ? Colors.red : Colors.blue,

onPressed: () {

setState(){ // trigger rebuild of the button

pressed = !pressed;

}

}

);

}Code Snippet 4: Red button in Flutter (Declarative)

Is it not very inefficient to re-render the entire Widget every time we change the State? That was the first question I had when learning about this topic. But I was pleased to learn, that Flutter uses something called “RenderObjects” to improve performance similar to Reacts [22] virtual DOM.

“RenderObjects persist between frames and Flutter’s lightweight Widgets tell the framework to mutate the RenderObjects between States. The Flutter framework handles the rest.” [27]

This section will give you a better understanding of how programming in Flutter [1] actually works. You will learn what Widgets [30] are, what types of Widgets Flutter has and lastly what exactly the Widget Tree is.

One sentence that is impossible to avoid when researching Flutter is:

“In Flutter, everything is a Widget.” [30]

But that is not really helpful, is it? Personally, I like Didier Boelens definition of Flutter Widgets better:

| 📙 | Widget | A visual component (or a component that interacts with the visual aspect of an application) [31] |

|---|

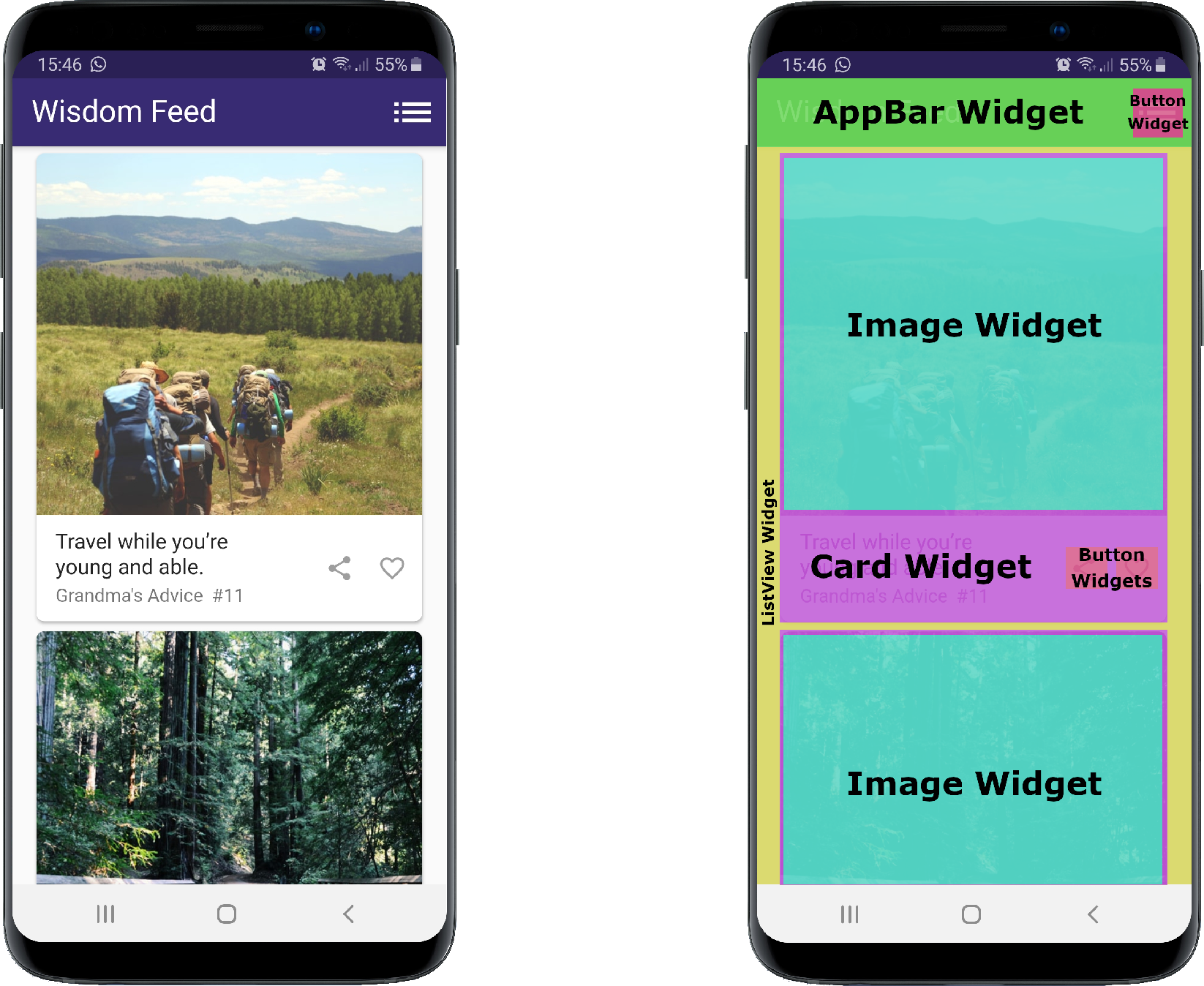

Let’s have look at an example, this is the Wisgen app [11], it displays an endless feed of wisdoms combined with vaguely thought-provoking stock images:

Figure 8: Wisgen Widgets [11]

All UI-Components of the app are Widgets. From high-level stuff like the AppBar and the ListView down to to the granular things like texts and buttons (I did not highlight every Widget on the screen to keep the figure from becoming overcrowded). In code, the build method of a card Widget would look something like this:

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Card(

shape: RoundedRectangleBorder( //Declare corners to be rounded

borderRadius: BorderRadius.circular(7),

),

elevation: 2, //Declare shadow drop

child: Column( //The child of the card are displayed in a column Widget

children: <Widget>[

_Image(_wisdom.imgUrl), //First child

_Content(_wisdom), //Second Child

],

),

);

}Code Snippet 5: Simplified Wisgen card Widget build method [11]

The _Image class generates a Widget that contains the stock image. The _Content class generates a Widget that displays the wisdom text and the buttons on the card. An important thing to note is that:

| ⚠ | Widgets in Flutter are always immutable [30] |

|---|

The build method of any given Widget can be called multiple times a second. And how often it is called exactly is never under your control, it is controlled by the Flutter Framework [32]. To make this rapid rebuilding of Widgets efficient, Flutter forces us developers to keep the build methods lightweight by making all Widgets immutable [33]. This means that all variables in a Widget have to be declared as final. They are initialized once and can not change over time. But your app never consists out of exclusively immutable parts, does it? Variables need to change, data needs to be fetched and stored. Almost any app needs some sort of mutable data. As mentioned in the previous chapter, in Flutter such data is called State [12]. No worries, how Flutter handles mutable State will be covered in the section Stateful Widgets down below, so just keep on reading.

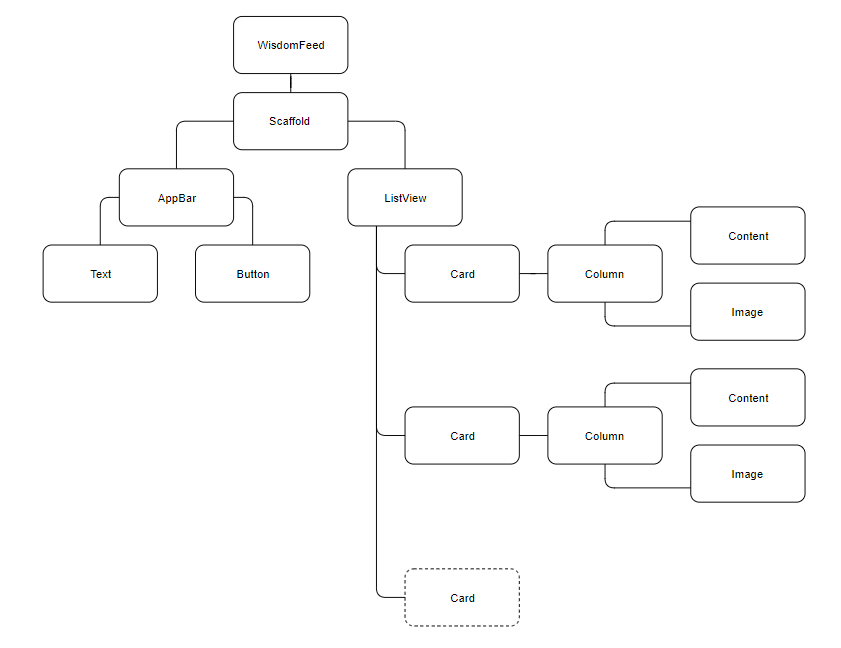

When working with Flutter, you will inevitably stumble over the term Widget Tree, but what is a Widget Tree? A UI in Flutter is nothing more than a tree of nested Widgets. Let’s have a look at the Widget Tree of our example from figure 8. Note the card Widgets on the right-hand side of the diagram. There you can see how the code from snippet 5 translates to Widgets in the Widget Tree.

Figure 9: Wisgen Widget Tree [11]

If you have previously built an app with Flutter, you have definitely encountered BuildContext [34]. It is passed in as a variable in every Widget build method in Flutter.

| 📙 | BuildContext | A reference to the location of a Widget within the tree structure of all the Widgets that have been built [31] |

|---|

The BuildContext contains information about each ancestor leading down to the Widget that the BuildContext belongs to. It is an easy way for a Widget to access all its ancestors in the Widget Tree. Accessing a Widgets descendants through the BuildContext is possible, but not advised and inefficient. So in short: It s very easy for a Widget at the bottom of the tree to get information from Widgets at the top of the tree but not vice-versa [31]. For example, the image Widget from figure 9 could access its ancestor card Widget like this:

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

//going up the Widget Tree:

//(Image [me]) -> (Column) -> (Card) [!] first match, so this one is returned

Card ancestorCard = Card.of(context);

return CachedNetworkImage(

...

);

}Code Snippet 6: Hypothetical Wisgen image Widget [11]

Alright, but what does that mean for me as a Flutter developer? It is important to understand how data in Flutter flows through the Widget Tree: Downwards. You want to place information that is required by multiple Widgets above them in the tree, so they can both easily access it through their BuildContext. Keep this in mind, for now, I will explain this in more detail in the chapter Architecting a Flutter App.

There are three types of Widgets in the Flutter Framework. I will now showcase their differences, their lifecycles, and their respective use-cases.

This is the most basic of the three and likely the one you’ll use the most when developing an app with Flutter. Stateless Widgets [32] are initialized once with a set of parameters and those parameters will never change from there on out. Let’s have a look at an example. This is a simplified version of the card Widget from figure 8:

class WisdomCard extends StatelessWidget {

static const double _cardElevation = 2;

static const double _cardBorderRadius = 7;

final Wisdom _wisdom;

WisdomCard(this._wisdom);

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {...}

...

}Code Snippet 7: Simplified Wisgen card Widget class [11]

As you can see, it has some constant values for styling, a wisdom object that is passed into the constructor and a build method. The wisdom object contains the wisdom text and the hyperlink to the stock image.

One thing I want to point out here is that even if all fields are final in a StatelessWidget, it can still change to a degree. A ListView Widget is also a Stateless for example. It has a final reference to a list. Things can be added or removed from that list without the reference in the ListView Widget changing. So the ListView remains immutable and Stateless while the things it displays can change [35].

The Lifecycle of Stateless Widgets is very straight forward [31]:

class MyWidget extends StatelessWidget {

///Called first

///

///Use for initialization if needed

MyClass({ Key key }) : super(key: key);

///Called multiple times a second

///

///Keep lightweight (!)

///This is where the actual UI is build

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

...

}

}Code Snippet 8: Stateless Widget Lifecycle

I explained what State is in the Chapter Thinking Declaratively. But just as a reminder:

| 📙 | State | Any data that can change over time [12] |

|---|

A Stateful Widget [13] always consists of two parts: An immutable Widget and a mutable State. The immutable Widget’s responsibility is to hold onto that State, the State itself has the mutable data and builds the actual UI element [36]. Let’s have a look at an example. This is a simplified version of the WisdomFeed from Figure 8. The WisdomBloc is responsible for generating and caching wisdoms that are then displayed in the Feed. More on that in the chapter Architecting a Flutter App.

///Immutable Widget

class WisdomFeed extends StatefulWidget {

@override

State<StatefulWidget> createState() => WisdomFeedState();

}

///Mutable State

class WisdomFeedState extends State<WisdomFeed>{

WisdomBloc _wisdomBloc; //Mutable / Not final (!)

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

//This is where the actual UI element/Widget is build

...

}

}Code Snippet 9: Simplified Wisgen WisdomFeed [11]

If you are anything like me, you will ask yourself: “why is this split into 2 parts? The StatefulWidget is not really doing anything.” Well, The Flutter Team wants to keep Widgets always immutable. The only way to keep this statement universally true is to have the StatefulWidget hold onto the State but not actually be the State [36], [37].

State objects have a long lifespan in Flutter. They will stick around during rebuilds or even if the Widget that they are linked to gets replaced [36]. So in this example, no matter how often the WisdomFeed gets rebuild and no matter if the user switches pages, the cached list of wisdoms (WisdomBloc) will stay the same until the app is shut down.

The Lifecycle of State Objects/StatefulWidgets is a little bit more complex. I will only showcase a boiled-down version here. It contains all the methods you’ll need for this guide. You can read the full Lifecycle here: Lifecycle of StatefulWidgets [37].

class MyWidget extends StatefulWidget {

///Called immediately when first building the StatefulWidget

@override

State<StatefulWidget> createState() => MySate();

}

class MyState extends State<MyWidget>{

///Called after constructor

///

///Called exactly once

///Use this to subscribe to Streams or for any initialization

@override

initState(){...}

///Called multiple times a second

///

///Keep lightweight (!)

///This is where the actual UI element/Widget is build

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context){...}

///Called once before the State is disposed (app shut down)

///

///Use this for your clean up and to unsubscribe from Streams

@override

dispose(){...}

}Code Snippet 10: State Objects/StatefulWidgets Lifecycle

Keep in mind, to improve performance, you always want to rely on as few Stateful Widgets as possible. There are essentially two reasons to choose a Stateful Widget over a Stateless one:

- The Widget needs to hold any kind of data that has to change during its lifetime.

- The Widget needs to dispose of anything or clean up after itself at the end of its lifetime.

I will not go in detail on Inherited Widgets [38] here. When using the BLoC library [39], which I will teach you in the chapter Architecting a Flutter-App, you will most likely never create an Inherited Widgets yourself. But in short: They are a way to expose data from the top of the Widget Tree to all their descendants. And they are used as the underlying technology of the BLoC library.

Asynchronous Programming is an essential part of any modern application. There will always be network calls, user inputs or any number of other unpredictable events that an app has to wait for. Luckily Dart [3] and Flutter [1] have a very good integration of Asynchronous Programming. This chapter will teach you the basics of Futures [3] and Streams [40]. The latter of these two will be especially important moving forward, as it one of the fundamental technologies used by the BLoC Pattern [7]. Throughout this chapter, I will be using the HTTP package [41] to make network requests. Communication with the Web is one of the most common use-cases for Asynchronous Programming, so I thought it would only be fitting.

Futures [3] are the most basic way of dealing with asynchronous code in Flutter. If you have ever worked with JavaScript’s Promises [42] before, they are basically the exact same thing. Here is a small example: This is a simplified version of the Wisgen ApiSupplier class. It can make requests to the AdviceSlip API [43] to fetch some new advice texts.

import 'package:http/http.dart' as http;

class ApiSupplier {

///Delivers 1 random advice as JSON

static const _adviceURI = 'https://api.adviceslip.com/advice';

Future<Wisdom> fetch() {

//Define the Future and what the result will look like

Future<http.Response> apiCall = http.get(_adviceURI);

//Define what will happen once it's resolved

return apiCall.then((response) => Wisdom.fromResponse(response));

}

}Code Snippet 11: Simplified Wisgen ApiSupplier (Futures) [11]

We call get() on the HTTP module and give it the URL it should request. The get() method returns a Future. A Future object is a reference to an event that will take place at some point in the future. We can give it a callback function with then(), that will execute once that event is resolved. The callback we define will get access to the result of the Future IE it’s type: Future<Type>. So here, Future<http.Response> apiCall is a reference to when the API call will be resolved. Once the call is complete, then() will be called and we get access to the http.Response. We tell the Future to transform the Response into a wisdom object and return the result, by adding this instruction as a callback to then() [44], [45]. We can also handle errors with the catchError() function:

import 'package:http/http.dart' as http;

class ApiSupplier {

///Delivers 1 random advice as JSON

static const _adviceURI = 'https://api.adviceslip.com/advice';

Future<Wisdom> fetch() {

Future<http.Response> apiCall = http.get(_adviceURI);

return apiCall

.then((response) => Wisdom.fromResponse(response))

.catchError((exception) => Wisdom.Empty);

}

}Code Snippet 12: Simplified Wisgen ApiSupplier (Futures with Error) [11]

If you have ever worked with Promises or Futures before, you know that this can get really ugly really quickly: callbacks nested in callbacks. Luckily Dart supports the async & await keywords [46], which give us the ability to structure our asynchronous code the same way we would if it was synchronous. Let’s take the same example as in snippet 11:

import 'package:http/http.dart' as http;

class ApiSupplier {

///Delivers 1 random advice as JSON

static const _adviceURI = 'https://api.adviceslip.com/advice';

Future<Wisdom> fetch() async {

http.Response response = await http.get(_adviceURI);

return Wisdom.fromResponse(response);

}

}Code Snippet 13: Simplified Wisgen ApiSupplier (Async & Await) [11]

We can use the await keyword to tell Flutter to wait at on specific point until a Future is resolved. In this example, Flutter waits until the http.Response has arrived and then proceeds to transform it into a wisdom. If we want to use the await keyword in a function, we have to mark the function as async. This forces the return type of the function to be a Future because if we wait during the function, the function can not return instantly, thus it has to return a Future [47]. Error handling in async function can be done with try/catch:

import 'package:http/http.dart' as http;

class ApiSupplier {

///Delivers 1 random advice as JSON

static const _adviceURI = 'https://api.adviceslip.com/advice';

Future<Wisdom> fetch() async {

try {

http.Response response = await http.get(_adviceURI);

return Wisdom.fromResponse(response);

} catch (exception) {

return Wisdom.Empty;

}

}

}Code Snippet 14: Simplified Wisgen ApiSupplier (Async & Await with Error) [11]

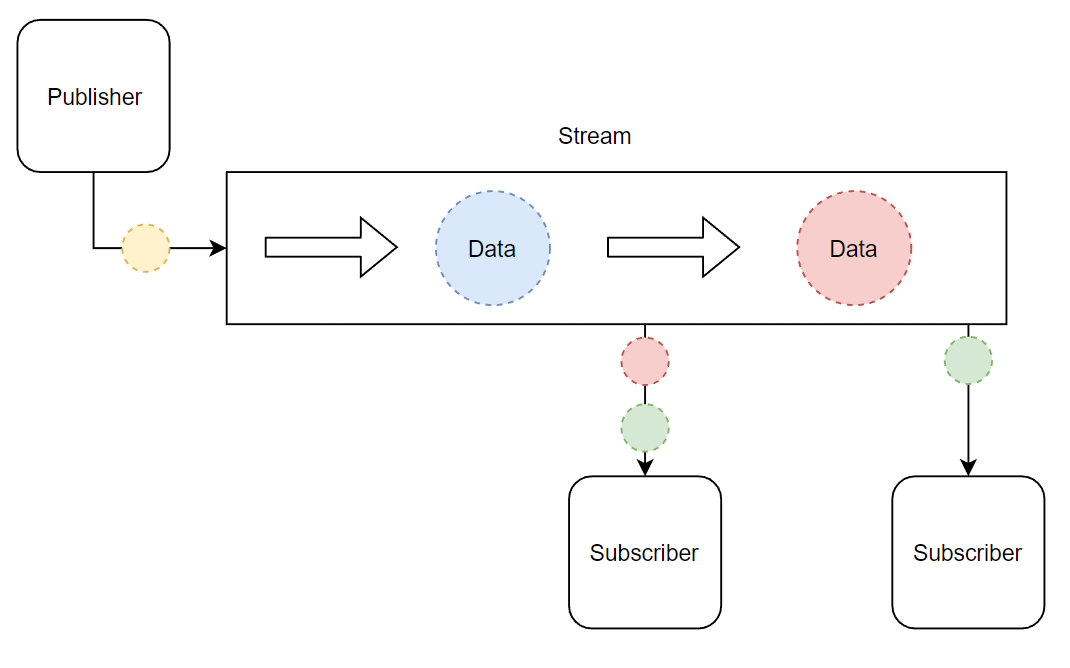

Streams [40] are one of the core technologies behind reactive programming [48]. And we’ll use them heavily in the chapter Architecting a Flutter app. But what exactly are Streams? As Andrew Brogdon put’s it in one of Google’s official Dart tutorials, Streams are to Future what Iterables are to synchronous data types [49]. You can think of Streams as one continuous flow of data. Data can be put into the Stream, other parties can subscribe/listen to a given Stream and be notified once a new piece of data enters the Stream.

Figure 10: Data Stream

Let’s have a look at how we can implement Streams in Dart. First, we initialize a StreamController [40] to generate a new Stream. The StreamController gives us access to a Sink, that we can use to put data into the Stream and the actual Stream object, which we can use to read data from the Stream:

main(List<String> arguments) {

StreamController<int> _controller = StreamController();

for(int i = 0; i < 5 ; i++){

_controller.sink.add(i);

}

_controller.stream.listen((i) => print(i));

_controller.close(); //don't forget to close the stream once you are done

}Code Snippet 15: Stream of Ints

0

1

2

3

4Code Snippet 16: Stream of Ints output

Important Side Note:

| ⚠ | Streams in Dart are single subscription by default. So if you want multiple subscribers you need to initialize it like this: StreamController streamController = new StreamController.broadcast();

|

|---|

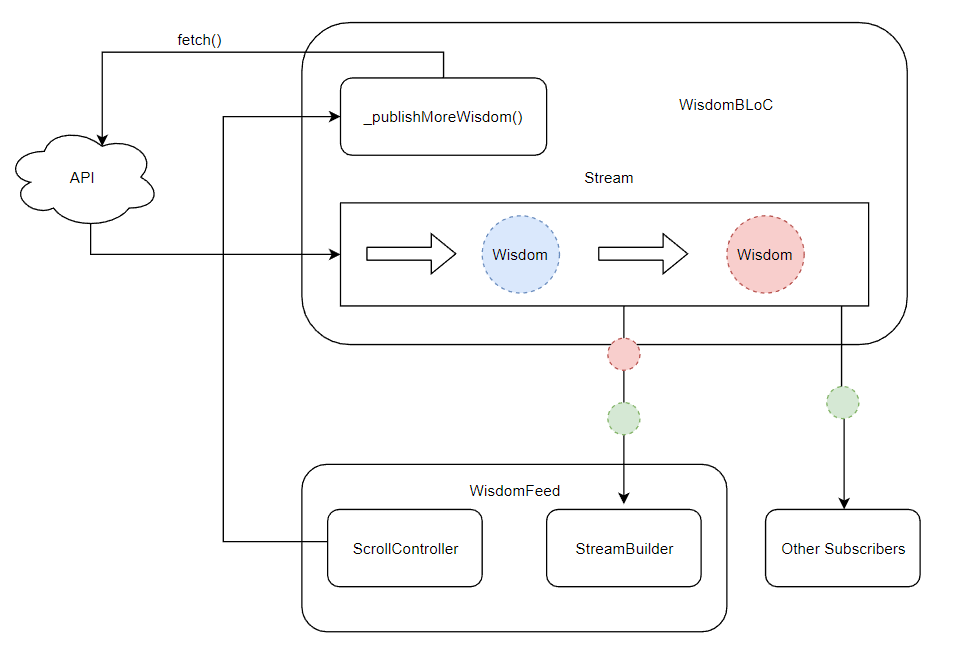

Let’s have a look at a more complex example. In Wisgen, our wisdoms are delivered to the UI via a Stream. Whenever we run out of wisdoms to display, a request is sent to a class that fetches new wisdom form our API [43] and publishes them in a stream. Once the API response comes in, the UI gets notified and receives the new list of wisdoms. This approach is part of the BLoC Pattern [7] and I will explain it in detail in the chapter Architecting a Flutter app. For now, this is a simplified version of the class that is responsible for streaming wisdom:

class WisdomBloc {

final ApiSupplier _api = new Api();

List<Wisdom> _oldWisdoms = new List();

//Stream

final StreamController _streamController = StreamController<List<Wisdom>>;

StreamSink<List<Wisdom>> get _wisdomSink => _streamController.sink; //Data In

Stream<List<Wisdom>> get wisdomStream => _streamController.stream; //Data out

///Called from UI to tell the BLoC to put more wisdom into the Stream

publishMoreWisdom() async {

//Fetch a wisdom form the API (Snippet 14)

Wisdom fetchedWisdom = await _api.fetch();

//Appending the new wisdoms to the current State

List<Wisdom> newWisdoms = _oldWisdoms..add(fetchedWisdom);

_wisdomSink.add(newWisdoms); //publish to stream

_oldWisdoms = newWisdoms;

}

///Called when UI is disposed

dispose() => _streamController.close();

}Code Snippet 17: Simplified Wisgen WisdomBLoC [11]

First, we create a StreamController and expose the Stream itself to enable the UI to subscribe to it. We also open up a private Sink, so we can easily add new wisdoms to the Stream. Whenever the publishMoreWisdom() function is called, the BLoC request a new wisdom from the API, waits until it is fetched, and then publishes it to the Stream. Let’s look at the UI side of things. This is a simplified version of the WisdomFeed in Wisgen:

class WisdomFeedState extends State<WisdomFeed> {

WisdomBloc _wisdomBloc;

///We Tell the WisdomBLoC to fetch more data based on how far we have scrolled down

///the list. That is why we need this Controller

final _scrollController = ScrollController();

static const _scrollThreshold = 200.0;

@override

void initState() {

_wisdomBloc = new WisdomBloc();

_wisdomBloc.publishMoreWisdom(); //Dispatch initial event

_scrollController.addListener(_onScroll);

super.initState();

}

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Scaffold(

body: StreamBuilder(

stream: _wisdomBloc.wisdomStream,

builder: (context, AsyncSnapshot<List<Wisdom>> snapshot) {

//Show Error message

if (snapshot.hasError) return ErrorText(state.exception);

//Show loading animation

if (snapshot.connectionState == ConnectionState.waiting) return LoadingSpinner();

//Create ListView of wisdoms

else return _listView(context, snapshot.data);

},

),

);

}

Widget _listView(BuildContext context, List<Wisdom> wisdoms) {

return ListView.builder(

itemBuilder: (BuildContext context, int index) {

return index >= wisdoms.length

? LoadingCard()

: WisdomCard(wisdom: wisdoms[index]);

},

itemCount: wisdoms.length + 1,

controller: _scrollController,

);

}

@override

void dispose() {

_wisdomBloc.dispose();

_scrollController.dispose();

super.dispose();

}

///Dispatching fetch events to the BLoC when we reach the end of the list

void _onScroll() {

final maxScroll = _scrollController.position.maxScrollExtent;

final currentScroll = _scrollController.position.pixels;

if (maxScroll - currentScroll <= _scrollThreshold) {

_wisdomBloc.publishMoreWisdom(); //Publish more wisdoms

}

}

...

}Code Snippet 18: Simplified Wisgen WisdomFeed with StreamBuilder [11]

Alright, let’s go through this step by step:

First, we initialize our WisdomBloc in the initSate() method. This is also where we set up a ScrollController [50] that we can use to determine how far down the list we have scrolled [51]. I won’t go into the details here, but the controller enables us to call publishMoreWisdom() on the WisdomBloc whenever we are near the end of our list. This way we get infinite scrolling.

In the build() method, we use Flutter’s StreamBuilder Widget [52] to link our UI to our Stream. We give it our Stream and it provides a builder method. This builder method receives a Snapshot containing the current State of the Stream whenever the State of the Stream changes IE when new wisdom is added. We can use the Snapshot to determine when the UI needs to display a loading animation, an error message or the actual list. When we receive new wisdoms from our Stream through the Snapshot, we continue to the listView() method.

Here we use the list of wisdoms to create a ListView containing cards that display wisdoms. You might have wondered why we Stream a list of wisdoms and not just individual wisdoms. This ListView is the reason. If we where streaming individual wisdoms we would need to combine them into a list here. Streaming a complete list when using a StreamBuilder to create infinite scrolling is also the recommended approach by the Flutter Team [53].

Finally, once the app is closed down, the dispose() method is called and we dispose of our Stream and ScrollController.

Figure 11: Streaming Wisdom from BLoC to WisdomFeed [11]

Streams have two keywords that are very similar to the async & await of Futures: async* & yield [40]. If we mark a function as async* the return type has to be a Stream. In an async* function we get access to the async keyword (which we already know) and the yield keyword, which is very similar to a return, only that yield does not terminate the function but instead adds a value to the Stream. This is what an implementation of the WisdomBloc from snippet 17 could look like with async*:

Stream<List<Wisdom>> streamWisdoms() async* {

Wisdom fetchedWisdom = await _api.fetch();

//Appending the new wisdom to the current State

List<Wisdom> newWisdoms = _oldWisdoms..add(fetchedWisdom);

yield newWisdoms; //Publish to Stream

_oldWisdoms = newWisdoms;

}Code Snippet 19: Simplified Wisgen WisdomBLoC with async* [11]

This marks the end of my introduction to Streams. It can be a challenging topic wrap your head around at first so if you still feel like you want to learn more I can highly recommend this article by Didier Boelens [48] or this 8-minute tutorial video by the Flutter Team [49]

I just wanted to end this chapter by showing you how the ApiSupplier class of Wisgen [11] actually looks like and give some input of why it looks the way it does:

import 'dart:convert';

import 'dart:math';

import 'package:flutter/material.dart';

import 'package:wisgen/models/advice_slips.dart';

import 'package:wisgen/models/wisdom.dart';

import 'package:wisgen/repositories/supplier.dart';

import 'package:http/http.dart' as http;

///[Supplier] that caches [Wisdom]s it fetches from an API and

///then provides a given amount of random entries.

///

///[Wisdom]s Supplied do not have an Image URL

class ApiSupplier implements Supplier<List<Wisdom>> {

///Advice SLip API Query that requests all (~213) text entries from the API.

///We fetch all entries at once and cache them locally to minimize network traffic.

///The Advice Slip API also does not provide the option to request a selected amount of entries.

///That's why I think this is the best approach.

static const _adviceURI = 'https://api.adviceslip.com/advice/search/%20';

List<Wisdom> _cache;

final Random _random = Random();

@override

Future<List<Wisdom>> fetch(int amount, BuildContext context) async {

//if the cache is empty, request data from the API

if (_cache == null) _cache = await _loadData();

List<Wisdom> res = List();

for (int i = 0; i < amount; i++) {

res.add(_cache[_random.nextInt(_cache.length)]);

}

return res;

}

///Fetches Data from API and coverts it to wisdoms

Future<List<Wisdom>> _loadData() async {

http.Response response = await http.get(_adviceURI);

AdviceSlips adviceSlips = AdviceSlips.fromJson(json.decode(response.body));

List<Wisdom> wisdoms = List();

adviceSlips.slips.forEach((slip) {

wisdoms.add(slip.toWisdom());

});

return wisdoms;

}

}Code Snippet 20: Actual Wisgen ApiSupplier [11]

The AdviceSlips class was generated with a JSON to Dart converter [54]. The generated class has a fromJson() function that makes it easy to populate it’s data fields with the JSON response. I used this class instead of implementing a method in the Wisdom class because I did not want a direct dependency from my entity class to the AdviceSlip JSON structure. This is the generated class, you don’t need to read it all, I just want to give you an idea of how it looks like:

import 'package:wisgen/models/wisdom.dart';

///Generated class to handle JSON input from AdviceSlip API.

///I used this tool: https://javiercbk.github.io/json_to_dart/.

class AdviceSlips {

String totalResults;

String query;

List<Slips> slips;

AdviceSlips({this.totalResults, this.query, this.slips});

AdviceSlips.fromJson(Map<String, dynamic> json) {

totalResults = json['total_results'];

query = json['query'];

if (json['slips'] != null) {

slips = List<Slips>();

json['slips'].forEach((v) {

slips.add(Slips.fromJson(v));

});

}

}

Map<String, dynamic> toJson() {

final Map<String, dynamic> data = Map<String, dynamic>();

data['total_results'] = this.totalResults;

data['query'] = this.query;

if (this.slips != null) {

data['slips'] = this.slips.map((v) => v.toJson()).toList();

}

return data;

}

}

///Generated class to handle JSON input from AdviceSlip API.

///I used this tool: https://javiercbk.github.io/json_to_dart/.

///A Slip can be converted directly into a Wisdom object (this is a function I added myself)

class Slips {

String advice;

String slipId;

Slips({this.advice, this.slipId});

Slips.fromJson(Map<String, dynamic> json) {

advice = json['advice'];

slipId = json['slip_id'];

}

Map<String, dynamic> toJson() {

final Map<String, dynamic> data = Map<String, dynamic>();

data['advice'] = this.advice;

data['slip_id'] = this.slipId;

return data;

}

///Not generated

Wisdom toWisdom() {

return Wisdom(

id: int.parse(slipId),

text: advice,

type: "Advice Slip",

);

}

}Code Snippet 21: Wisgen AdviceSlips [11]

The Most central topic of architecting a Flutter app [1] is State Management [12]. Where does my State sit, who needs access to it, and how do they access it? This chapter aims to answer those questions. You will learn about the two types of State, you will be introduced to the three most popular State Management Solutions and you will learn one of those State Management Solutions (BLoC [7]) in detail. You will also learn how to use the BLoC State Management Solution in a clean and scalable four-layered architecture.

I want to differentiate these two terms. Within the Flutter community, State Management and Architecture are often used synonymously, but I think we should be careful to do so. State Management is, as the name indicates, managing the State of an application. This can be done with the help of a technology or a framework [12], [55]. Architecture, on the other hand, is the overarching structure of an app. A set of rules that an app conforms to [56]. Any architecture for a Flutter application will have some sort of State Management, but State Management is not an architecture by itself. I just want you to keep this in mind for the following chapters.

The Flutter documentation [12] differentiates between two types of State: Ephemeral State & App State. Ephemeral State is State that is only required in one location IE inside of one Widget. Examples would be: scroll position in a list, highlighting of selected elements or the color change of a pressed button. This is the type of State that we don’t need to worry about that much or in other words, there is no need for a fancy State Management Solution for Ephemeral State. We can simply use a Stateful Widget with some variables and manage Ephemeral State that way [12]. The more interesting type of State is App State. This is information that is required in multiple locations/by multiple Widgets. Examples would be user data, a list of favorites or a shopping cart. App State management is going to be the focus of this chapter.

Figure 12: Ephemeral State vs App State decision tree [12]

Other than many mobile development frameworks, Flutter [1] does not impose any kind of architecture or State Management Solution on its developers. This open-ended approach has lead to multiple State Management Solution and a hand full of architectural approaches spawning from the community [57]. Some of these approaches have even been endorsed by the Flutter Team itself [12]. I decided to focus on the BLoC pattern [7] for this guide. But I do want to showcase some alternatives and explain why exactly I ended up choosing BLoC.

I will showcase the State Management Solutions using one example of App State from the Wisgen App [11]. Wisgen gives the user the option to add wisdoms to a favorite list. This list/State is needed by two parties:

- The ListView on the favorite page, so it can display all favorites.

- The button on every wisdom card so it can add a new favorites to the list and show if a given wisdom is a favorite.

Figure 13: Wisgen favorites list and favorite in feed [11]

Whenever the favorite button on any card is pressed, several Widgets [30] have to update. This is a simplified version of the Wisgen Widget Tree. The red highlights show the Widgets that need access to the favorite list, the heart shows a possible location from where a new favorite could be added.

Figure 14: Wisgen favorites WidgetTree [11]

The Provider Package [58] is a State Management Solution for Flutter published by Remi Rousselet in 2018. It has since then been endorsed by the Flutter Team on multiple occasions [59], [60] and Rousselet and the Flutter Team are now devolving it in cooperation. The package is basically a prettier interface for Inherited Widgets [38]. You can use Provider to expose State from a Widget at the top of the tree to any number of Widgets below it in the tree.

As a quick reminder: Data in Flutter always flows downwards. If you want to access data from multiple locations within your Widget Tree, you have to place it at one of their common ancestors so they can both access it through their BuildContexts [34]. This practice is called “lifting State up” and it is very common within declarative frameworks [61].

| 📙 | Lifting State up | Placing State at the lowest common ancestor of all Widgets that need access to it [61] |

|---|

The Provider Package is an easy way for us to lift State up. Let’s look at our example from figure 14: The first common ancestor of all Widgets in need of the favorite list is MaterialApp. So we will need to lift the State up to the MaterialApp Widget and then have our other Widgets access it from there:

Figure 15: Wisgen WidgetTree favorites with Provider [11]

To minimize re-builds the Provider Package uses ChangeNotifiers [62]. This way Widgets can subscribe/listen to the provided State and get notified whenever it changes. This is how an implementation of Wisgen’s favorite list would look like using Provider. “Favorites” is the class we will use to provide our favorite list globally. The notifyListeners() function will trigger rebuilds on all Widgets that listen to it.

class Favorites with ChangeNotifier{

//State

final List<Wisdom> _wisdoms = new List();

add(Wisdom w){

_wisdoms.add(w);

notifyListeners(); //Re-Build all Listeners

}

remove(Wisdom w){

_wisdoms.remove(w);

notifyListeners(); //Re-Build all Listeners

}

bool contains(Wisdom w) => _wisdoms.contains(w);

}Code Snippet 22: Hypothetical Favorites class that would be exposed through the Provider Package [11]

Now we can expose our Favorite class above MaterialApp in the WidgetTree using the ChangeNotifierProvider Widget:

void main() => runApp(MyApp());

class MyApp extends StatelessWidget {

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

//Providing Favorite class globally

return ChangeNotifierProvider(

builder: (_) => Favorites(),

child: MaterialApp(home: WisdomFeed()),

);

}

}Code Snippet 23: Providing Favorite class globally [11]

Now we can consume the Favorite class from any of the dependance of the ChangeNotifierProvider Widget. Let’s look at the favorite button as an example. We use the Consumer Widget to get access to the favorite list and everything below the Consumer Widget will be rebuild when the favorites list changes. The wisdom object is the wisdom displayed on the Card Widget.

...

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Expanded(

flex: 1,

child: Consumer<Favorites>( //Consuming global instance of Favorite class

builder: (context, favorites, child) => IconButton(

//Display Icon Button depending on current State

icon: Icon(favorites.contains(wisdom)

? Icons.favorite

: Icons.favorite_border),

color: favorites.contains(wisdom)

? Colors.red

: Colors.grey,

onPressed: () {

//Add/remove wisdom to/from Favorite class

if (favorites.contains(wisdom)) favorites.remove(wisdom);

else favorites.add(wisdom);

},

),

),

)

}

...Code Snippet 24: Consuming Provider in favorite button [11]

All in all, Provider is a great and easy solution to distribute State in a small Flutter application. But it is just that, a State Management Solution and not an architecture [59], [60], [63], [64]. Just the Provider package alone with no pattern to follow or an architecture to obey will not lead to a clean and manageable application. But no worries, I did not teach you about the package for nothing. Because Provider is such an efficient and easy way to distribute State, the BLoC package [39] uses it as an underlying technology for their approach.

Redux [65] is State Management Solution with an associated architectural pattern. It was originally built for React [22] in 2015 by Dan Abramov. It was late ported to Flutter by Brian Egan in 2017 [66]. Redux uses a Store as one central location for all business logic. This Store is put at the very top of the Widget Tree and then globally provided to all Widgets using an Inherited Widget. We extract as much logic from the UI as possible. It should only send actions to the Store (such as user inputs) and display the UI dependant on the current State of the Store. The Store has Reducer functions, that take in the previous State and an Action and return a new State. [61], [63], [67] So in Wisgen, the Dataflow would look something like this:

Figure 16: Wisgen Redux dataflow [11]

Let’s have a quick look at how an implementation of Redux would look like in Wisgen. Our possible Actions are:

- Adding a new wisdom to our favorites.

- Removing a wisdom from our favorites.

So this is what our Action classes would look like:

@immutable

abstract class FavoriteAction {

//Wisdom related to Action

final Wisdom _favorite;

get favorite => _favorite;

FavoriteAction(this._favorite);

}

class AddFavoriteAction extends FavoriteAction {

AddFavoriteAction(Wisdom favorite) : super(favorite);

}

class RemoveFavoriteAction extends FavoriteAction {

RemoveFavoriteAction(Wisdom favorite) : super(favorite);

}Code Snippet 25: Hypothetical Wisgen Redux Actions [11]

This what the Reducer function would look like:

// take in old State and Action

List<Wisdom> favoriteReducer(List<Wisdom> state, FavoriteAction action) {

//Determine how to change the State

if (action is AddFavoriteAction) state.add(action.favorite);

if (action is RemoveFavoriteAction) state.remove(action.favorite);

//Return new State

return state;

}Code Snippet 26: Hypothetical Wisgen Redux Reducer [11]

And this is how we would make the Store globally available:

void main() => runApp(MyApp());

class MyApp extends StatelessWidget {

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

//Create new Store from Reducer function

favoriteStore = new Store<List<Wisdom>>(

reducer: favoriteReducer,

initialState: new List(),

);

//Provide Store globally

return StoreProvider<List<Wisdom>>((

store: favoriteStore,

child: MaterialApp(home: WisdomFeed()),

);

}

//Snippet 26

List<Wisdom> favoriteReducer(List<Wisdom> state, FavoriteAction action) {...}

}Code Snippet 27: Providing Redux Store globally in Wisgen [11]

Now the favorite button from snippet 24 would be implemented like this:

...

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Expanded(

flex: 1,

child: StoreConnector( //Consume Store

converter: (store) => store.state, //No need for conversion, just need current State

builder: (context, favorites) => IconButton(

//Display Icon Button depending on current State

icon: Icon(favorites.contains(wisdom)

? Icons.favorite

: Icons.favorite_border),

color: favorites.contains(wisdom)

? Colors.red

: Colors.grey,

onPressed: () {

//Add/remove wisdom to/from favorites

if (favorites.contains(wisdom)) store.dispatch(AddFavoriteAction(wisdom));

else store.dispatch(RemoveFavoriteAction(wisdom));

},

),

),

)

}

...Code Snippet 28: Consuming Redux Store in favorite button [11]

I went back and forth on this decision a lot. Redux is a great State Management Solution with some clear guidelines on how to integrate it into a Reactive application [68]. It also enables the implementation of a clean three-layered architecture (View - Store - Data) [61]. Didier Boelens recommends to just stick to a Redux architecture if you are already familiar with its approach from other cross-platform development frameworks like React [22] and Angular [69] and I very much agree with this advice [63]. I have previously never worked with Redux and I decided to use BLoC over Redux because:

- It was publicly endorsed by the Flutter Team on multiple occasions [7], [12], [53], [59], [70]

- It also has clear architectural rules [7]

- It also enables the implementation of a layered architecture [71]

- It was developed by one of Flutter’s Engineers [7]

- It does not end up with one giant Store for the business logic. Instead, we spread the business logic out into multiple BLoCs with separate responsibilities [63]

BLoC is an architectural pattern that functions as a State Management Solution. It was designed by Paolo Soares in 2018 [7]. Its original purpose was to enable code sharing between Flutter [1] and Angular Dart [72] applications. This chapter will give you an in-depth understanding of what the BLoC Pattern is and how it works. You will learn how to implement it using the BLoC Package [39] by Felix Angelov. And Finally, you will learn how to use the BLoC Pattern to achieve a scalable four-layered architecture for your application.

When Soares designed the BLoC Pattern, he was working on applications in both Flutter and Angular Dart. He wanted a pattern that enabled him to hook up the same business logic to both Flutter and Angular Dart apps. His idea was to remove business logic from the UI as much as possible and extract it into its own classes, into BLoCs (Business Logic Components). The UI should only send Events to BLoCs and display the UI based on the State of the BLoCs. Soares defined, that UI and BLoCs should only communicate through Streams [40]. This way the developer would not need to worry about manually telling the UI to redraw. The UI can simply subscribe to a Stream of State [12] emitted by a BLoC and change based on the incoming State [7], [48], [53], [70].

| 📙 | BLoC | Business Logic Component [7] |

|---|

| 🕐 | TLDR | The UI should be kept free of business logic. The UI only publishes Events to a BLoC and subscribes to a Stream of State emitted by a BLoC |

|---|

Figure 17: Bloc turning input Events to a Stream of State [70]

That’s all well and good, but why should you care? An application that follows the rules defined by the BLoC pattern will…

- have all its business logic in one place.

- have business logic that functions independently of the UI.

- have a UI that can be changed without affecting the business Logic.

- have easily testable business logic.

- rely on few rebuilds, as the UI only rebuilds when the State related to that UI changes.

- have an App-State with very predictable transitions as the pattern enforces a single way for State to change throughout the entire application.

[7], [39], [48], [63], [64]

To gain those promised advantages, you will have to follow these 8 rules Soares defined for the BLoC Pattern [7]:

- Input/Outputs are simple Sinks/Streams only.

- All dependencies must be injectable and platform agnostic.

-

No platform branching.

- No

if(IOS) then doThis().

- No

- The actual implementation can be whatever you want if you follow 1-3.

- Each “Complex Enough” Widget has a related BLoC.

- You will have to define what “Complex Enough” means for your app.

- Widgets do not format the inputs they send to the BLoC.

- Because formating is business logic.

- Widgets should display the BLoCs State/output with as little formatting as possible.

- Sometimes a little formatting is inevitable, but more complex things like currency formating is business logic and should be done in a BLoC.

- If you do have platform branching, It should be dependent on a single bool State/output emitted by a BLoC.

Figure 18: What a BLoC looks like [48]

Alright, Now that you know what the BLoC Pattern is, let’s have a look at how it looks in practice. I am using the BLoC package [39] for Flutter by Felix Angelov, as it removes a lot of the boilerplate code we would have to write if we would implement our own BLoCs from scratch and because it was publicly endorsed by the Flutter Team [73]. I am going to use the same example of App State as I did in the previous chapter: The favorite list in Wisgen [11]. First, let’s have a look at how the Bloc Pattern will interact with Wisgen on a more abstract scale:

Figure 19: Bloc and Wisgen Widget Tree [11]

These are the “Events” that can be sent to the BLoC by the UI. It is a common practice to use inheriting classes for Events. This way we can communicate intent through the name of the class and add some data for the Event to carry in its members. This approach of implementing Events is very similar to Redux’s Actions [65].

@immutable

abstract class FavoriteEvent {

final Wisdom _favorite;

get favorite => _favorite;

FavoriteEvent(this._favorite);

}

///Adds a given [Wisdom] to the [FavoriteBloc] when dispatched

class FavoriteEventAdd extends FavoriteEvent {

FavoriteEventAdd(Wisdom favorite) : super(favorite);

}

///Removes a given [Wisdom] from the [FavoriteBloc] when dispatched

class FavoriteEventRemove extends FavoriteEvent {

FavoriteEventRemove(Wisdom favorite) : super(favorite);

}Code Snippet 29: Favorite Events in Wisgen [11]

Now the arguably most interesting part of an implementation of the BLoC Pattern, the BLoC class itself. We extend the BLoC class provided by the Flutter BLoC package. It takes in the type of the Events that will be sent to the BLoC and the type of the State that will be emitted by the BLoC Bloc<Event, State>:

///Responsible for keeping track of the Favorite list.

///

///Receives [FavoriteEvent] to add/remove favorite [Wisdom] objects

///from its list.

///Broadcasts complete list of favorites every time it changes.

class FavoriteBloc extends Bloc<FavoriteEvent, List<Wisdom>> {

@override

List<Wisdom> get initialState => List<Wisdom>();

//Called when the BLoC receives an Event

@override

Stream<List<Wisdom>> mapEventToState(FavoriteEvent event) async* {

List<Wisdom> newFavorites = List()..addAll(currentState);

//Determine how to manipulate the State based on the Event

if (event is FavoriteEventAdd) newFavorites.add(event.favorite);

if (event is FavoriteEventRemove) newFavorites.remove(event.favorite);

//Emit new State

yield newFavorites;

}

}Code Snippet 30: Favorite BLoC in Wisgen [11]

As I mentioned before, the BLoC package for Flutter uses the Provider package [58]. This means that we can provide our BLoC to the rest of our Widget Tree in the same way we learned in the chapter State Management Alternatives. By the rule of “lifting State up”, we have to place the favorite BLoC at the lowest common ancestor of all Widgets that need access to it. So in our case at MaterialApp:

void main() => runApp(MyApp());

class MyApp extends StatelessWidget {

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

//Globally Providing the Favorite BLoC as it is needed on multiple pages

return BlocProvider(

builder: (BuildContext context) => FavoriteBloc(),

child: MaterialApp(home: WisdomFeed()),

);

}

}Code Snippet 31: Providing a BLoC Globally in Wisgen [11]

Now we can access the BLoC from all descendants of the BlocProvider Widget. This is the favorite button in Wisgen. It changes shape and color based on the State emitted by the FavoriteBLoC and it dispatches Events to the BLoC to add and remove favorites. The wisdom object is the wisdom displayed on the Card Widget.

...

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Expanded(

flex: 1,

//This is where we subscribe to the FavoriteBLoC

child: BlocBuilder<FavoriteBloc, List<Wisdom>>(

builder: (context, favorites) => IconButton(

//Display Icon Button depending on current State

//Re-build when favorite list changes

icon: Icon(favorites.contains(wisdom)

? Icons.favorite

: Icons.favorite_border),

color: favorites.contains(wisdom)

? Colors.red

: Colors.grey,

onPressed: () {

//Grab FavoriteBloc through BuildContext

FavoriteBloc favoriteBloc = BlocProvider.of<FavoriteBloc>(context);

//Add/remove Wisdom to/from favorites (dispatch events)

if (favorites.contains(wisdom)) favoriteBloc.dispatch(RemoveFavoriteEvent(wisdom));

else favoriteBloc.dispatch(AddFavoriteEvent(wisdom));

},

),

),

)

}

...Code Snippet 32: Accessing a BLoC in Wisgen [11]

Now that we understand how to implement the BLoC Pattern [7], lets’ have a look at how we can use it to achieve a four-layered architecture with one-way dependencies [71]:

Figure 20: Four-Layered BLoC architecture

This is the layer that our user directly interacts with. It is the Widget Tree of our application, all Widgets of our app sit here. We need to keep this layer as stupid as possible, No business logic and only minor formating.

This is where all our BLoCs reside. All our business logic sits in this layer. The communication between this layer and the UI Layer should be limited to Sinks and Streams:

Figure 21: Widget BLoC communication

For this Layer, all platform-specific dependencies should be injectable. To achieve this, the Flutter community [39], [57], [71], [74] mostly uses the Repository Pattern [75] or as “Uncle Bob” would say: Boundary Objects [76]. Even if this pattern is not an explicit part of BLoC, I personally think it is a very clean solution. Instead of having BLoCs directly depend on platform-specific interfaces, we create Repository interfaces for the BLoCs to depend on:

///Generic Repository that fetches a given amount of T

abstract class Supplier<T>{

Future<T> fetch(int amount, BuildContext context);

}Code Snippet 33: Wisgen platform-agnostic Repository [11]

The actual implementation of the Repository can then be injected into the BLoC.

This Layer consist of platform-agnostic interfaces. Things like Data Base, Service, and Supplier (Snippet 33).

These are the actual implementations of our Repositories. Platform-specific things like a Database connector or a class that makes API calls.

To give you a better understanding of how this architecture works in practice, I will walk you through how Wisgen [11] is built using the BLoC Pattern and a four-layered architecture.

Figure 22: Wisgen architecture with dependencies [11]

In the UI Layer, we have all the Widgets that make up Wisgen. Three of those actually consume State from the BLoC Layer, so those are the only ones I put in figure 22. The Wisdom Feed displays an infinite list of wisdoms. Whenever the user scrolls close to the bottom of the list, the Wisdom Feed sends a Request-Event to the Wisdom BLoC [51]. This Event causes the Wisdom BLoC to fetch more data from its Repository. You can see the Repository interface in snippet 33. This way the Wisdom BLoC just knows it can fetch some data with its Repository and it does not care where the data comes from or how the data is fetched. In our case, the Repository could be implemented to either load some wisdoms from a local list or fetch some wisdoms from an API. I already covered the implementation of the API Repository class in the chapter Asynchronous Flutter if you want to remind yourself again. When the Wisdom BLoC receives a response from its Repository, it publishes the new wisdoms to its Stream [40] and all listening Widgets will be notified.

Figure 23: Wisgen dataflow [11]

I already covered how the favorite list works in detail in this chapter, so I won’t go over it again. The Storage BLoC keeps a persistent copy of the favorite list on the device. It receives a Load-Event once on start-up, loads the old favorite list from its Storage, and adds it to the Favorite BLoC though Add-Events. It also listens to the Favorite BLoC and updates the persistent copy of the favorite list every time the Favorite Bloc emits a new State:

///Gives access to the 2 Events the [StorageBloc] can receive.

///

///It is an enum because the 2 Events both don't need to carry additional data.

///[StorageEvent.load] tells the [StorageBloc] to load the

///favorite list from its [Storage].

///[StorageEvent.wipe] tells the [StorageBloc] to wipe

///any favorites on its [Storage].

enum StorageEvent { load, wipe }

///Responsible for keeping a persistent copy of the favorite list on its [Storage].

///

///It is injected with a [FavoriteBLoC] on creation.

///It subscribes to the [FavoriteBLoC] and writes the favorite list to

///its [Storage] device every time a new State is emitted by the [FavoriteBLoC].

///When the [StorageBLoC] receives a [StorageEvent.load], it loads a list of [Wisdom]s

///from its [Storage] device and pipes it into the [FavoriteBLoC] though [FavoriteEventAdd]s

///(This usually happens once on start-up).

///Its State is [dynamic] because it never needs to emit it.

class StorageBloc extends Bloc<StorageEvent, dynamic> {

Storage _storage = SharedPreferenceStorage();

FavoriteBloc _observedBloc;

StorageBloc(this._observedBloc) {

//Subscribe to BLoC

_observedBloc.state.listen((state) async {

await _storage.save(state);

});

}

@override

dynamic get initialState => dynamic;

///Called every time a new [StorageEvent] comes in.

@override

Stream<dynamic> mapEventToState(StorageEvent event) async* {

if (event == StorageEvent.load) await _load();

if (event == StorageEvent.wipe) _storage.wipeStorage();

}

///Load the old favorite list form [Storgae].

_load() async {

List<Wisdom> loaded = await _storage.load();

if (loaded == null || loaded.isEmpty) return;

loaded.forEach((f) {

_observedBloc.dispatch(FavoriteEventAdd(f));

});

}

//Injection ---

set storage(Storage storage) => _storage = storage;

set observedBloc(FavoriteBloc observedBloc) => _observedBloc = observedBloc;

}Code Snippet 34: Wisgen Storage BLoC [11]

Storage is also a platform-agnostic interface and it looks like this:

///Generic Repository for read/write Storage device.

abstract class Storage<T>{

Future<T> load();

save(T data);

///Wipe the Storage Medium of all T.

wipeStorage();

}Code Snippet 35: Wisgen platform-agnostic Repository: Storage [11]

In Wisgen, I built an implementation of Storage that communicates with Androids Shared Preferences [77] and saves the favorite list as a JSON:

///[Storage] that gives access to Androids Shared Preferences

///(a small, local, persistent key-value-store).

class SharedPreferenceStorage implements Storage<List<Wisdom>> {

///Key is used to access store.

static const String _sharedPrefKey = "wisgen_storage";

@override

Future<List<Wisdom>> load() async {

final prefs = await SharedPreferences.getInstance();

List<String> strings = prefs.getStringList(_sharedPrefKey);

if (strings == null || strings.isEmpty) return null;

//Decode all JSON strings we fetched from the

//Preferences and add them to the result.

List<Wisdom> wisdoms = List();

strings.forEach((s) {

Wisdom w = Wisdom.fromJson(jsonDecode(s));

wisdoms.add(w);

});

return wisdoms;

}

@override

save(List<Wisdom> data) async {

if (data == null || data.isEmpty) return;

final prefs = await SharedPreferences.getInstance();

//Encode data to JSON Strings

List<String> strings = List();

data.forEach((wisdom) {

strings.add(json.encode(wisdom.toJson()));

});

//Overwrite Preferences with new List

prefs.setStringList(_sharedPrefKey, strings);

}

@override

wipeStorage() async {

final prefs = await SharedPreferences.getInstance();

prefs.remove(_sharedPrefKey);

}

}Code Snippet 36: Wisgen’s Storage implementation for SharedPreferences [11]

Testing has become an essential part of developing any large scale application and there is strong evidence that writing tests leads to a higher code quality [78]. This chapter aims to give you a brief introduction to how testing in Flutter [1] works and more specifically, how to test an app that implements the BLoC Pattern [7].

Flutters official test library [79] differentiates between three types of tests:

Unit Tests can be run very quickly. They can test any function of your app, that does not require the rendering of a Widget [80]. Their main use-case is to test business logic or in our case: BLoCs [7].

Widget Tests are used to test small Widget Sub-Trees of your application. They run relatively quickly and can test the behavior of a given UI [80].

Integration/Driver Tests run your entire application in a virtual machine or on a physical device. They can test user-journeys and complete use-cases. They are very slow and “prone to braking”[80].

Figure 24: Flutter test comparison [81]

I will focus on Unit Tests for this guide. The Flutter Team recommends that the majority of Flutter tests should be Unit Test [80], [81]. The fact that they are quick to write and quick to execute makes up for their relatively low confidence. In addition to this, because we are using the BLoC Pattern, our UI shouldn’t contain that much testable code anyways. Or to paraphrase the BLoC pattern creator: We keep our UI so stupid we don’t need to test it [7]. First, we have to import the test library [79] and the mockito package [82] in our pubspec.yaml:

dev_dependencies:

mockito: ^4.1.1

flutter_test:

sdk: flutterCode Snippet 37: Pubspec.yaml Test Imports

flutter_test offers the core testing capabilities of Flutter. mockito is used to mock up dependencies. All our tests should sit in a directory named “test” on the root level of our app directory. If we want to place them somewhere else, we have to specify their location every time we want to run them.

Figure 25: Wisgen test directory [11]

| ⚠ | All test files have to end with the postfix "_test.dart" to be recognized by the framework [80]. |

|---|

Now we can start writing our tests. For this example, I will test the favorite BLoC of Wisgen [11]:

void main() {

///Related test are grouped together

///to get a more readable output

group('Favorite Bloc', () {

FavoriteBloc favoriteBloc;

setUp((){

//Run before each test

favoriteBloc = new FavoriteBloc();

});

tearDown((){

//Run after each test

favoriteBloc.dispose();

});

test('Initial State is an empty list', () {

expect(favoriteBloc.currentState, List());

});

...

});

}Code Snippet 38: Wisgen Favorite BLoC Tests 1 [11]

We can use the group() function to group related tests together. This way the output of our tests is more neatly formated [80]. setUp() is called once before every test, so it is perfect for initializing our BLoC [83]. tearDown() is called after every test, so we can use it to dispose of our BLoC. The test() function takes in a name and a callback with the actual test. In our test, we check if the State of the favorite BloC after initialization is an empty list. expect() takes in the actual value and the value that is expected: expect(actual, matcher). We can run all our tests using the command flutter test.

Now a more relevant topic when working with the BLoC Pattern, the testing of Streams [40]:

void main() {

group('Favorite Bloc', () {

FavoriteBloc favoriteBloc;

setUp((){...}); //Snippet 38

tearDown((){...}); //Snippet 38

test('Initial State is an empty list', () {...}); //Snippet 38

test('Stream many Events and see if the State is emitted in the correct order', () {

//Set Up

Wisdom wisdom1 = Wisdom(id: 1, text: "Back up your pictures", type: "tech");

Wisdom wisdom2 = Wisdom(id: 2, text: "Wash your ears", type: "Mum's Advice");

Wisdom wisdom3 = Wisdom(id: 3, text: "Travel while you're young", type: "Grandma's Advice");

//Testing

favoriteBloc.dispatch(FavoriteEventAdd(wisdom1));

favoriteBloc.dispatch(FavoriteEventAdd(wisdom2));

favoriteBloc.dispatch(FavoriteEventRemove(wisdom1));

favoriteBloc.dispatch(FavoriteEventAdd(wisdom3));

//Result

expect(

favoriteBloc.state,

emitsInOrder([

List(), //BLoC Library BLoCs emit their initial State on creation.

List()..add(wisdom1),

List()..add(wisdom1)..add(wisdom2),

List()..add(wisdom2),

List()..add(wisdom2)..add(wisdom3)

]));

});

});

}Code Snippet 39: Wisgen Favorite BLoC Tests 2 [11]

In this test, we create three wisdoms and add/remove them from the favorite BLoC by sending the corresponding Events. We use the emitsInOrder() matcher to tell the framework that we are working with a Stream and looking for a specific set of Events to be emitted in order [83]. The Flutters test framework also offers many other Stream matchers besides emitsInOrder() [84]:

- emits() matches a single data Event.

- emitsError() matches a single error Event.

- emitsDone matches a single done Event.

- emitsAnyOf() consumes events matching one (or more) of several possible matchers.

- emitsInAnyOrder() works like emitsInOrder(), but it allows the matchers to match in any order.

- neverEmits() matches a Stream that finishes without matching an inner matcher.

- And more [84]

As mentioned before, Mockito [82] can be used to mock dependencies. The BLoC Pattern forces us to make all platform-specific dependencies of our BLoCs injectable [7]. This comes in very handy when testing BLoCs. For example, the wisdom BLoC of Wisgen fetches data from a given Repository. Instead of testing the Wisdom BLoC in combination with its Repository, we can inject a mock Repository into the BLoC. This way we can test one bit of logic at a time. In this example, we use Mockito to test if our wisdom BLoC emits new wisdoms after receiving a fetch event:

//Creating Mocks using Mockito

class MockRepository extends Mock implements Supplier<Wisdom> {}

class MockBuildContext extends Mock implements BuildContext {}

void main() {

group('Wisdom Bloc', () {

WisdomBloc wisdomBloc;

MockRepository mockRepository;

MockBuildContext mockBuildContext;

setUp(() {

wisdomBloc = WisdomBloc();

mockRepository = MockRepository();

mockBuildContext = MockBuildContext();

//Inject Mock

wisdomBloc.repository = mockRepository;

});

tearDown(() {

//Run after each test

wisdomBloc.dispose();

});

test('Send Fetch Event and see if it emits correct wisdom', () {

//Set Up ---

List<Wisdom> fetchedWisdom = [

Wisdom(id: 1, text: "Back up your Pictures", type: "tech"),

Wisdom(id: 2, text: "Wash your ears", type: "Mum's Advice"),

Wisdom(id: 3, text: "Travel while you're young", type: "Grandma's Advice")

];

//Telling the Mock Repo how to behave

when(mockRepository.fetch(20, mockBuildContext))

.thenAnswer((_) async => fetchedWisdom);

List expectedStates = [

IdleWisdomState(new List()), //BLoC Library BLoCs emit their initial State on creation

IdleWisdomState(fetchedWisdom)

];

//Testing ---

wisdomBloc.dispatch(FetchEvent(mockBuildContext));

//Result ---

expect(wisdomBloc.state, emitsInOrder(expectedStates));

});

});

}Code Snippet 40: Wisgen Wisdom BLoC Tests with Mockito [11]

First, we create our Mock classes. For this test, we need a mock Supplier-Repository and a mock BuildContext [34]. In the setUp() function, we initialize our BLoC and our mocks and inject the mock Repository into our BLoC. In the test() function, we tell our mock Repository to send a list of three wisdoms when its fetch() function is called. Now we can send a fetch event to the BLoC, and check if it emits the correct states in order.

| ⚠ | By default, all comparisons in Dart work based on references and not base on values [83], [85] |

|---|

Wisdom wisdom1 = Wisdom(id: 1, text: "Back up your Pictures", type: "tech");

Wisdom wisdom2 = Wisdom(id: 1, text: "Back up your Pictures", type: "tech");

print(wisdom1 == wisdom2); //falseCode Snippet 41: Equality in Flutter

This can be an easy thing to trip over during testing, especially when comparing States emitted by BLoCs. Luckily, Felix Angelov released the Equatable package in 2019 [85]. It’s an easy way to overwrite how class equality is handled. If we make a class extend the Equatable class, we can set the properties it is compared by. We do this by overwriting its props attribute. This is used in Wisgen to make the States of the wisdom BLoC compare based on the wisdom they carry:

@immutable

abstract class WisdomState extends Equatable {}

///Broadcasted from [WisdomBloc] on network error.

class WisdomStateError extends WisdomState {

final Exception exception;

WisdomStateError(this.exception);

@override

List<Object> get props => [exception]; //compare based on exception.

}

///Gives access to current list of [Wisdom]s in the [WisdomBloc].

///

///When the BLoC receives a [WisdomEventFetch] during this State,

///it fetches more [Wisdom] from it [Supplier].

///When done it emits a new [IdleSate] with more [Wisdom].

class WisdomStateIdle extends WisdomState {

final List<Wisdom> wisdoms;

WisdomStateIdle(this.wisdoms);

@override

List<Object> get props => wisdoms; //compare based on wisdoms.

}Code Snippet 42: Wisgen Wisdom States with Equatable [11]

If we wouldn’t use Equatable, the test form snippet 40 could not functions properly, as two states carrying the same wisdom would still be considered different by the test framework.

| 🕐 | TLDR | If you don’t want your classes to be compared base on their reference, use the Equatable package [85] |

|---|

I want to start this chapter with a great quote from Dart’s official style guide:

“A surprisingly important part of good code is good style. Consistent naming, ordering, and formatting helps code that is the same look the same.” [86]

This chapter will teach you some of the current best practices, conventions, and tips when writing Dart code [3] and Flutter applications [1] in general. That being said, the Dart team has published its own comprehensive guide [86] on writing effective Dart. I will be highlighting some of the information in that guide here, but I will mainly be focusing on the aspects that are unique to Dart and might be a bit counter-intuitive when coming from other languages or frameworks.