Connor Eaton

Metis: Project McNulty. January, 30, 2019.

Human and machine interaction is becoming increasingly foundational to our society. From highly efficent automated call centers to suprisingly intimate companion machines, learning how to conduct life along side machines will be one of the major advancements and challenges of the 21st century. One of the principal components of fostering this cultural transition will be building machines that can predict our emotions, however irrational and imcomprehensible they may sometimes seem. We generally understand machines, so it would be good if they generally understood us.

In this project, I built a classification model to predict positive or negative emotion in human speech.

The data source for this project will be the Crowd-sourced Emotional Mutimodal Actors Dataset (CREMA-D). It can be found here:

https://github.com/CheyneyComputerScience/CREMA-D/tree/master/docs

This data contains ~7,500 .mp3 files containing recordings of actors saying the same 12 sentences with six different emotions. Other tables containing demographic data per actor and emotional tone per file were merged with audio files and cleaned in a postgress database.

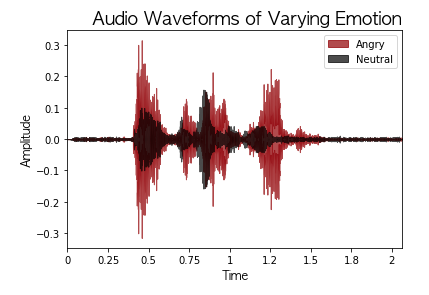

Numerous spectral features were extracted from waveforms (see below) as arrays from the raw mp3 files using the Librosa library. To prepare features for modeling, the mean and standard deviation was computed for each feature and merged into my postgreSQL database.

The final spectral features I included in my model were: chroma (standard deviation), contrast (mean), energy (mean), energy (standard deviation), MFCC (standard deviation), flatness (standard deviation), and zero cross rate (mean & standard deviation). My target was positive emotion (neutral/happy) and negative emotion (anger/disgust).

All data cleaning and engineering was completed in postgress. For feature extraction and compilation, a .py script was written to input audio files and return a data frame of features. Modeling and visualizations were done in a .ipynb file. All of the above can be found in this repo.

To compelte this project, I used python, jupyter notebooks, postgreSQL, pandas, numpy, matplotlib, scikit-learn, Ipython, Librosa, and XGBoost.

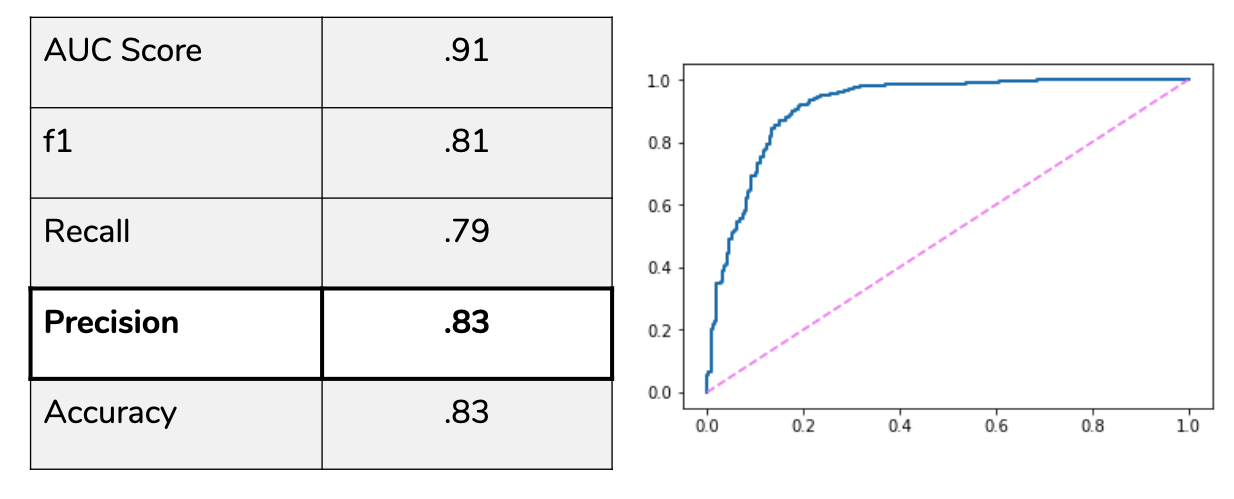

I constructed a variety of models in this project, including Logistic Regression, K Nearest Neihbors, Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost, all optimized with GridSearchCV. Parameters were tuned to optimize precision, which was my metric of concern so that my model limited false positives. XGBoost was chosen as my final model because it was the strongest performer across the board, with precision and accuracy at .83.

Below is the ROC curve, along with the rest of the performance metrics on my model.

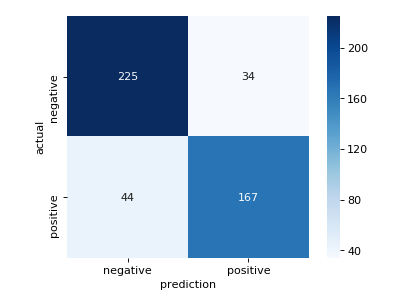

Below is a confusion matrix for my model predicting on my testing data. Note the low occurance of False Positives, which is what I wanted to avoid.

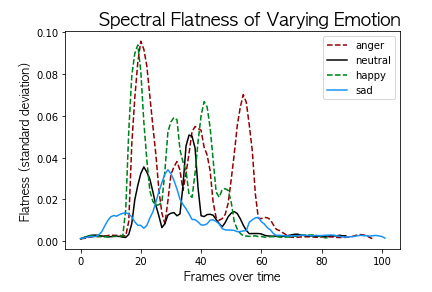

I originally set out to build a model that predicted two classes, positive or negative emotion. From my experience in emotional analysis, a ratio of positive:negative emotion is an incredibly powerful and efficient way to analyze affect. However, this may have not been the best approach. Notice in the image below how polar emotions like happiness and anger look fairly similar compared to neutral and sadness in terms of spectral flatness. This illustrates a positive class emotion (happiness) appearing more similar to a negative class emotion (anger) than its fellow positive emotions (neutral). Forcing spectral features from emotions that we intuitively group together in similar classes may not be optimal for machine learning, and predicting a class for each emotion on its own may increase overall performance.

Too late in the scope of the project timeline, I discovered the high-level benefits of pyAudioAnalysis. Building my model from the ground up in Librosa was a great exercise, but pyAudioAnalysis (https://github.com/tyiannak/pyAudioAnalysis) provides high-level functions to extract features and construct high performance classification models with relative ease. With pyAudioAnalysis, I was able to train a SVM model on the same training data used before and predict the emotional class of my own recorded speech utterances with probabilities in the 0.70-0.80 range with just a few lines of code. This is a very promising future direction for my work in emotional analysis.

In addition, natural language processing and deep learning was outside of the scope of this project. This prevented me from diving into text, image, or video emotional analysis, which I am looking forward to diving into in the future.

Even though I built a classification model to predict emotion with 83% accuracy, I’m not necessarily happy about it. Internally, I carry two polarizing perceptions of this technology, of which I have only scratched the surface. The romantic within me feels that the subjectivity, mystery, and power of emotion is one of the last frontiers of the human experience left unspoiled. If we strip emotion down to synapses and waveform statistics, will that degrade the potency of art, love, and beauty? However, the technologist in me envisions a future with human-centered AI, where our daily lives are full of interactions with emotionally perceptive machines that enhance the human experience.

This is an amazing era to study the psychology and machine learning and I am so grateful to be somewhere in the middle. This intersection will greatly influence the way we interact with machines in the coming years, and I look forward to playing my role in shaping a meaningful future.