-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 40

oauth design

This document describes the method by which Mozilla web services (called "RP"s, Relying Parties) can allow their users to "Sign In With Your Firefox Account". The RP server will receive proof that the user controls the given FxA, as well as credentials that grant it certain access to data on other servers on behalf of that user.

This uses an OAuth2 flow and a new "fxa-oauth-server" to issue and validate tokens. RPs can use these tokens to convince other servers (known as "Delegated Services") to accept their requests.

The RP web page redirects the browser to a special login page on the FxA Content Server. The user then enters their email address and FxA password on this page, which verifies them and allocates a secret code, then redirects the browser back to the RP page. The code is then used by the RP backend server to verify the user's identity and obtain the OAuth token it will use for subsequent requests.

Before the user even turns on the computer, several things must happen behind the scenes. Each RP which wants to use FxA logins must be registered with the fxa-oauth-server. They provide a callback_uri, and receive a client_id and a shared client_secret.

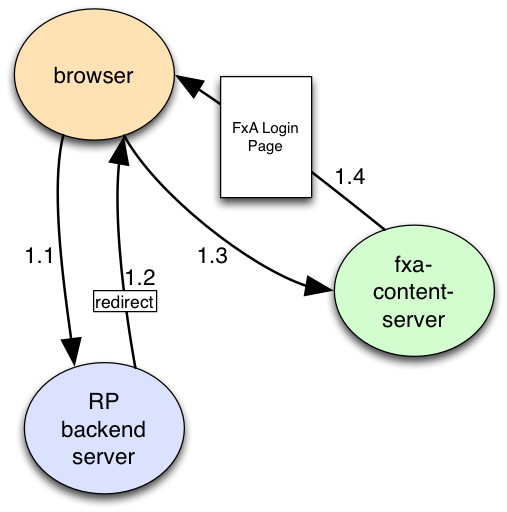

The real login process starts when the user directs her browser at an RP like the Mozilla Marketplace. The "RP Backend Server" delivers a web page which we call the "RP Frontend Page". This includes a "Sign In With Your Firefox Account" link.

When this link is clicked (1.1), the page redirects the browser (1.2) to a page (1.3) on the fxa-content-server, and includes the following query arguments (which might be included in the page ahead of time, generated by JS with some XHR calls at the moment the login button is clicked, or generated by the RP server via an intermediate redirect):

- client_id: which pre-registered RP is asking for tokens

- redirect_uri: an RP URL to which the browser will be returned after login

- state: a nonce used to bind the outbound redirect with the eventual return

- scope (optional): space-separated list of desired authorities. (remember that spaces are URL-encoded as "+")

For example, the browser might be redirected to: https://login.accounts.firefox.org/login.html?client_id=3a903bd6a81a2cdc&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fmarketplace.mozilla.com%2Flogin2.html&state=64c4e4dcfedd9c2d25e8fe8ce017aa31

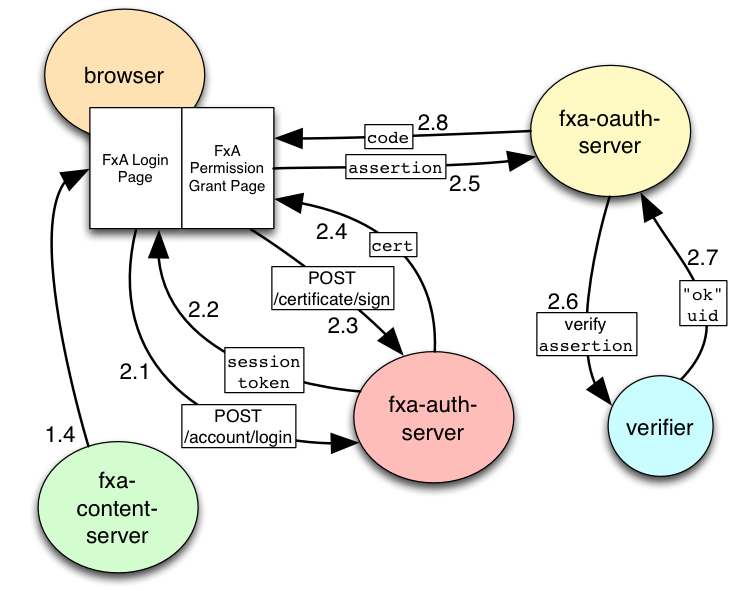

The fxa-content-server then serves a login.html page (1.4) which describes the name of the RP asking for access (derived from the client_id), the sort of delegated access they're asking for (scope), and asks the user for their email address and password. The content-server page uses email+password in XHR requests (2.1) to the fxa-auth-server's /account/login API endpoint to obtain a session token (2.2), generates a public key, and uses both token and key to obtain a signed certificate (2.4). It uses the cert to create a signed assertion (with audience pointing at the fxa-oauth-server), then forgets the keys and session token (and maybe also destroys the session?). The page then uses an API on the new fxa-oauth-server (2.5) to exchange the assertion for a "code" (which is bound to the client_id and scope) (2.8) and verifies that the requested redirect_uri matches the origin registered for that client. Finally, the page redirects the browser back to the RP's redirect_uri, along with several query arguments:

- state: matches the original redirect argument, to bind them together

- code: allocated by fxa-oauth-server

(To convert the assertion into a code, the fxa-oauth-server submits the assertion to a browserid verifier that knows the fxa-auth-server's public key (2.6), which verifies the signatures and returns the uid embedded in the certificate (2.7). The fxa-oauth-server then allocates a code, and associates it in an internal table with the account uid and the client_id of the RP. The code is returned to the browser, and the table entry will be used later.)

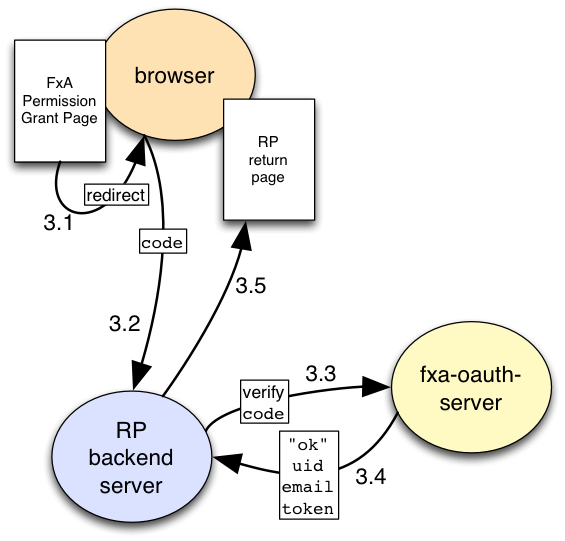

The RP backend server sees the argument-augmented redirect_uri request (3.2), checks that state matches a flow that it remembers, and extracts code. It them makes an HTTPS POST (3.3) to a different fxa-oauth-server endpoint (meant for RP backend servers, rather than web browsers), which includes the following arguments:

- client_id: same as before

- client_secret: the shared secret, to convince fxa-oauth-server that this is the named+registered RP and not a stranger or some other registered RP (1).

- code: extracted from the return redirect URL

The fxa-oauth-server looks up the client_id, verifies client_secret, then looks up code to make sure it is bound to the given client_id. If everything is ok, it retrieves the scope that was previously requested and removes code from the table. It then allocates a new OAuth2 "access_token", binding it to the client_id and scope. The POST response (3.4) is a JSON blob with these properties:

- access_token

- scopes: list of scope identifiers

- token_type: the literal string "

bearer"

If client_secret or code are wrong, or the code is not bound to the right client_id, the fxa-oauth-server will return an error.

The RP receives the POST response. If fxa-oauth-server signalled and error, the client request was invalid, and the RP returns an error page that invites the user to try to log in again. If it indicates success, the RP stores at least access_token in a database, and typically links it to a new RP session token, which is then returned to the user's browser as a cookie. RP pages can then deliver the RP-session-token cookie (plus suitable CSRF defenses) to validate subsequent RP requests.

(still WIP)

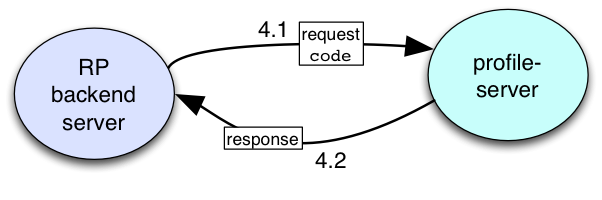

When the RP Backend Server wants to use some of the power it's been granted by the user, it makes an HTTPS-protected request to the corresponding API endpoint (4.1) and includes the access_token in the request (either in a header, or a query argument, depending upon the API) (2). The Delegated Service which hosts this API endpoint submits the token to the fxa-oauth-server's "validate-token" API, which either returns a tuple of (account-id, scopes), or an error if the token is invalid. The delegated service then has enough information to decide whether to honor the RP's request or not.

(still WIP)

The protocols defined in https://github.com/mozilla/fxa-auth-server/wiki/onepw-protocol enables basic login: specifically, a client application (in conjunction with a human who knows the account password) can use HTTPS APIs and some brief cryptographic operations to talk to the fxa-auth-server to obtain a signed BrowserID certificate. This certificate can be used to create BrowserID assertions, and these assertions can be used to convince specific RPs (named in the "Audience" of each assertion) that the bearer (i.e. the client app) rightfully has control over the numbered FxA account named in the certificate.

Persona/BrowserID offers several privacy and useability improvements over traditional third-party login systems. First, the use of public-key signatures allows RPs to verify certificates from IdPs without first establishing a shared HMAC secret (i.e. RPs do not have to register with the IdP). Second, the use of two separate public-key signatures allows RPs to verify assertions without revealing (to the IdP) which user is signing in.

However the close relationship between the FxA IdP (fxa-auth-server) and the Mozilla services using these logins (RPs) negates these benefits.

(the

Since BrowserID assertions

we need more than this

third-party convincing

delegated authority

web flow

assertion-length: Persona uses internal hidden iframes, to improve privacy (a redirect flow would reveal referrer and redirect URIs to the IdP). Iframes require postMessage. postMessage enables long messages, enabling assertions. But Iframes are difficult for compatibility (JSChannel has all sorts of weird fallbacks for older browsers), whereas redirects are easy. IdP/RP privacy is moot, removing that constraint, making redirects easier to implement compatibly, which imposes length restriction on the message, which prohibits passing assertions through a redirect, requiring "code". (that would still allow using "code" to fetch an assertion)

-

(1): it might be better to use the shared secret as an HMAC key, instead of as a bearer token, but doing so is non-trivial and requires the fxa-oauth-server to store all of these secrets verbatim

-

(2): again, RP backend servers want to use a better proof-of-knowledge technique when exercising the

access_tokenin requests to delegated services.